Thirty Years of Thrawn

Star Wars and the month of May have a deep connection. There's May the Fourth, which, thanks to some wordplay and some mistranslation, has become the official day of Star Wars. There's the fact that the six original Lucas films were all released in May. But they weren't the only important Star Wars stories released in May. Timothy Zahn's Heir to the Empire was first published on May 1st, 1991, thirty years ago today.

Heir to the Empire was not the first Star Wars book; the novelization of A New Hope actually was released months before the film, and that book's ghostwriter, Alan Dean Foster, would go on to adapt a discarded concept for Episode V into Splinter of the Mind's Eye, the first stand-alone Star Wars novel. But Heir to the Empire is better remembered, as the book that kicked off the uninterrupted cascade of novels that made up the bulk of the Expanded Universe, and as the first appearance of one of Star Wars' most enduring villains: Grand Admiral Thrawn.

In the decades since, Thrawn has appeared in books, comics, and animation, and, in the near future, it seems likely that he will appear on screen in live-action. To celebrate the character's anniversary, I've reviewed the media wherein Thrawn has appeared. Why has he become such a fan-favorite? How has he changed the broader Star Wars universe? And how has that broader universe changed him?

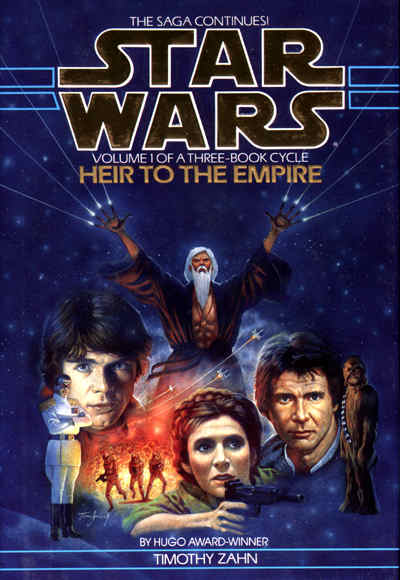

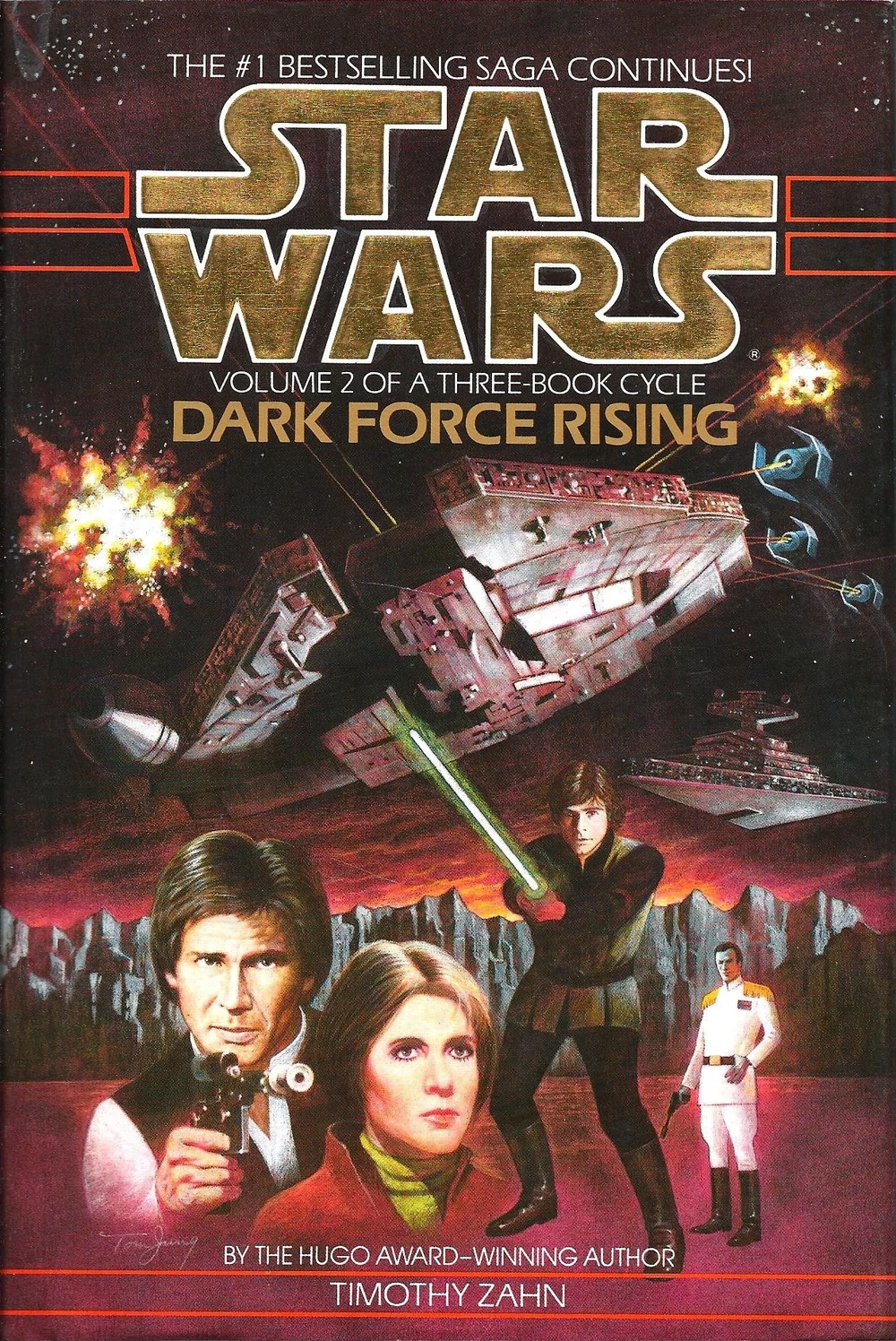

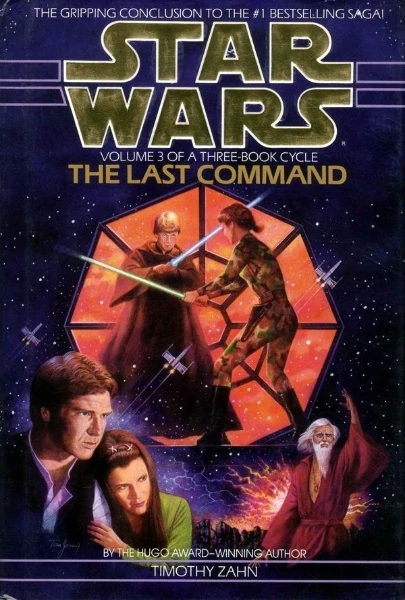

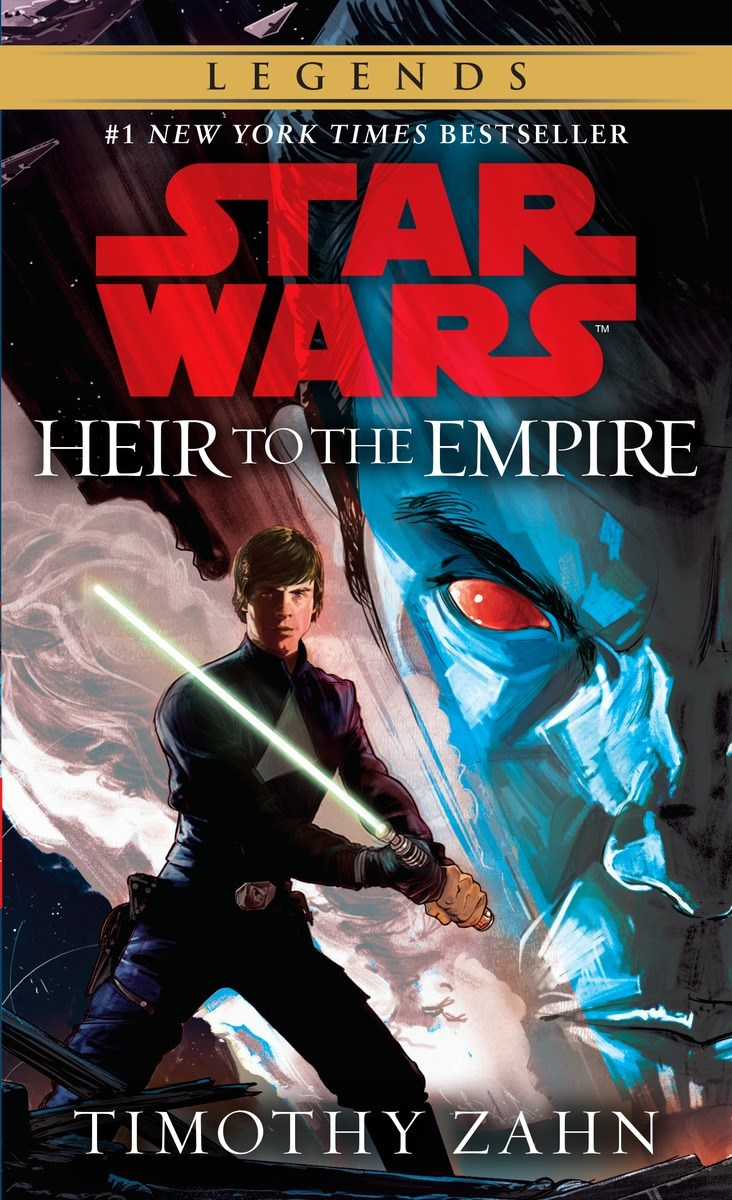

Original Covers for the Thrawn Trilogy | Art by Tom Jung

The Original (Thrawn) Trilogy [1991 - 1993]

Heir to the Empire was the first of these books in which Thrawn was the principal villain, which therefore came to be called the Thrawn Trilogy. I'll call it that or the Original Thrawn Trilogy, to differentiate it from the Canon Thrawn Trilogy, which we'll be getting to later.

As I said, the Thrawn Trilogy was not the first Star Wars story outside of the films. Beside Splinter of the Mind's Eye, there was a line of Star Wars comics produced by Marvel from 1977 to 1986, which told stories set between the films. 1985 saw the release of two Saturday morning cartoons, one about C-3PO and R2-D2, the other, which ran for a second season, about Wicket and his fellow Ewoks. The mid-'80s also saw the airing of a pair of low-budget TV movies about Ewoks. Two trilogies of books, one about Han Solo and one about Lando Calrissian came in the immediate aftermath of Return of the Jedi. And there might be one or two other things I'm forgetting.

While there are surely a non-zero number of Star Wars fans who got into Star Wars through these '80s-era stories, all these comics and cartoons weren't created to continue Star Wars, but to capitalize on it. By the late '80s, Star Wars was dormant. Lucas kept saying he had plans for a set of prequel films, but many fans at the time were convinced Star Wars was over.

What fans didn't know was that Lucas was in talks with publisher Bantam Spectra, an imprint of Random House, to put together a series of books serving as sequels to the films. At the top of Bantam's list of prospective authors was Timothy Zahn.

In a way, Zahn was the perfect choice to write these books. He was, and is, chiefly a writer of military sci-fi; he wrote star wars, so of course he could write Star Wars. But Zahn's books were...a little different from the Star Wars films. His Blackcollar Trilogy and his later Cobra trilogy both dealt with post-human supersoldiers in brutal wars against aliens. I haven't read those. I have read the excellent Cascade Point, which won Zahn the 1984 Hugo for Best Novella. That was set in space, but that's about where the similarities to Star Wars end. It was a very introspective character piece, with little in the way of grand battles or swashbuckling adventure.

Zahn was given a fair bit of freedom when creating the "authorized" continuation of Star Wars, though there were some guidelines: the books were to take place roughly five years after Return of the Jedi, no character explicitly killed in the film could make an appearance (they were saving that for Dark Empire, the comic series being produced at around the same time), the sourcebook for West End Games's Star Wars roleplaying game was to be used as a reference along with the films. Zahn's drafts were monitored, and a few changes were mandated as writing progressed. Zahn had run with Darth Vader's title Dark Lord of the Sith and introduced the Sith as a species enslaved to the Empire. These people could stay, but they would be re-named Noghri. Zahn could have an insane clone of a Jedi Master, but he couldn't be a clone of Obi-Wan Kenobi. Zahn also couldn't title the first book Wild Card, as the George R.R. Martin superhero anthology Wild Cards was a thing (and still is, going on 28 volumes at time of writing).

Still, Zahn navigated the difficulties of writing for Star Wars, and, in 1991, published Heir to the Empire, followed in subsequent years by Dark Force Rising and The Last Command. These three books saw great commercial success, and left an enduring mark on Star Wars. Thrawn came out of them, yes, but so did other classic characters, such as Mara Jade, Borsk Fey'lya, Gilad Pellaeon, Garm Bel Iblis, and Jacen and Jaina Solo. Zahn developed the Bothan species, establishing most of their attributes, save their name. He gave the name Coruscant to the galactic capital. Even if you haven't read the original Thrawn Trilogy, you've certainly encountered something from it in other Star Wars media.

So, Zahn's trilogy is important, but is it good? After all, it was written a while ago, before a lot of things about the Star Wars universe had been really nailed down. In short, yes, the Thrawn Trilogy is good. Upon reading it over again in preparation for writing this, I was impressed by how well it held up. Not as part of the canon, mind; even before the Disney buyout, the Thrawn Trilogy was strictly legacy content, what with its consistent references to a Clone Wars fought by the Old Republic and the Jedi against a cabal of mad scientists and their army of clones. Other little things, like Luke Skywalker looking out at the mountain range past the bounds of the Imperial City on Coruscant, will stick out as incorrect to the modern Star Wars fan. But, setting aside the knowledge of what came after, because it's hardly fair to blame Zahn for not writing in accordance with the post-Prequel understanding of the franchise in the early '90s, the Thrawn Trilogy remains one of the best post-Endor stories. Zahn wrote each of the existing characters well: his Luke Skywalker is a good-hearted Jedi Knight, able to hold his own now but still not a Master on the level of Obi-Wan or Yoda, yet. Han and Lando are both written believably, neither bland non-entities nor exaggerated cartoons of themselves, as they often can become, depending on the story or the writer. Leia, the trickiest of the original cast to get right, is done especially well. While she serves as a sort of living macguffin early on, she quickly gets an important sub-plot of her own, ultimately becoming the New Republic figure most responsible for Thrawn's defeat. New characters, like Mara Jade, Talon Karrde, Niles Ferrier, etc. fit into the story well alongside the characters from the films. (Jade was Zahn's second-most enduring character; she was arguably a bigger deal than Thrawn in the old EU, but she didn't fit in the Disney Canon, and Thrawn did, so he has taken the crown in recent years.)

Mara Jade's arc through the books is the element most like Lucas's films, since that's the part of the story wherein Luke Skywalker helps someone else gain redemption from evil influence. The rest of the Thrawn Trilogy is actually quite distinctly different from the films. The Star Wars Original Trilogy, and Star Wars films generally, can best be described as cool. Star Wars is a mashup of Flash Gordon, Kurosawa films, spaghetti westerns, WWII aerial dogfights, hot rods, NASA rockets, and anything else George Lucas and the other people working on the films thought was cool. While Zahn's books still include many of those elements, "cool" does not seem to be the motivating adjective in his writing. Zahn doesn't want his books to be considered "cool" so much as to be considered "clever".

Zahn's writing for Star Wars has a few hallmarks. Usually there will be at least one scene where someone is in disguise. Usually there's an action scene featuring some sort of exotic weapons, rather than just blades and guns. Usually, the plotlines of his books are looping and twisting, the true nature of events not being what they seemed at first. All these things that leave impressions on fans are clever things, things that display a lot of thought put into writing them.

Perhaps this is simply a matter of Zahn making books where Lucas, et al, were making movies. The Thrawn Trilogy includes many fantastical locales: a city carved of crystal, a casino aboard a submarine, a village built in the interwoven branches of titanic trees, a mining camp marching across the landscape on mechanical legs. These are all cool things, but we're only reading about them. We aren't seeing them like we saw a desert with two suns, or a space station the size of a moon, or a city floating in the clouds. We might imagine what something we read looks like, but we'll probably stop doing that once the scene gets going, so there's only so cool a place in a book can be. But, returning to that walking mining complex: being in a book means we can find that Lando Calrissian's Nomad City isn't just cool to picture in our minds; a book can take the time to explain how it must be able to move to keep out of the planet's harsh sunlight. Nomad City, we find in reading about it, is very clever.

Covers for the 2016 edition of the Thrawn Trilogy | Art by Rich Kelly

And, of course, the most clever thing in these clever books is Thrawn himself, whom I should probably get around to discussing. Thrawn was deliberately written in contrast to Darth Vader and the other Imperial leaders in the films. He is not prone to raging against his officers and is unconcerned with status and personal gain. His entire motivation is to establish Imperial order over the galaxy. He is, in these books, the model of an Imperial military commander. Zahn has said he wrote Thrawn as a leader who inspired loyalty in those under him, rather than fear. Though Thrawn had little tolerance for outright incompetence (just ask Cris Pieterson), he was not a harsh leader. He was willing to accept defeat in battle, giving up on major offensives rather quickly when his victory became uncertain, so as not to waste his resources.

While he is firmly the villain of the Thrawn Trilogy, you can see the potential for the more nuanced looks at Thrawn which Zahn has written more recently all the way back here, at the beginning. Thrawn isn't heroic, he isn't even terribly ethical, but he is a weirdly selfless sort of evil that makes him respectable, where the Emperor and most of his underlings were contemptable. Thrawn isn't good, but he seems like one who could rule the galaxy without inspiring wide-spread armed rebellion.

We never see any scenes from Thrawn's point of view in these books; his mind is a black box, whose outward effects are seen mostly from the perspective of Gilad Pellaeon, the captain of Thrawn's flagship, the Chimaera. This is a writing trick that gets used in a lot of old detective stories. The perspective character, the one through whose eyes and ears the reader witnesses the scene, is not a magnificent genius, they are simply constantly standing next to a magnificent genius, watching their inexplicable success, then hearing the magnificent genius explain their thought process like an illusionist explaining a magic trick. The perspective character is amazed at how magnificent the magnificent genius's genius is, and, because the perspective character is an audience surrogate, the reader is also amazed. This serves a three-fold purpose:

- The author can better boast of the magnificent genius's mental prowess this way. Having a separate character say "you are brilliant" generally comes of better than having the main character say "I am brilliant".

- Seeing something done, then understanding how it was done later, is more exciting than hearing how something will be done, then seeing it done. Again, it's like a magic trick. The reader is amazed to witness the impossible done, then again amazed that the impossible was actually possible all along.

- It makes it possible to write a plausible character who is much smarter than the author, which is difficult to do with a perspective character.

Altogether Thrawn was both something new and exciting in Star Wars and also a well-realized character in his own right. The Expanded Universe was off to a strong start.

In Thrawn's Wake [1993 - 1997]

Thrawn died at the end of the trilogy, but his uniqueness as a villain and the masterful way Zahn wrote him made him a fan-favorite character. So, even though he was killed, there was interest enough in the character for him to appear in more Star Wars properties throughout the '90s. Comic adaptations of the Thrawn Trilogy came quickly from Dark Horse, the comic publisher who got the Star Wars license that Marvel had abandoned in the mid-'80s. (Dark Horse, as I've alluded to, had as much of an impact in reviving Star Wars as Bantam Spectra did, with the Dark Empire and Tales of the Jedi series, both from Tom Veitch, also coming around this time. The former cast its own long shadow over later adventures of Luke, Han, and Leia; the latter established much about the early history of the Jedi and the Sith.)

Zahn wrote several prequel stories about Thrawn's career in Palpatine's service for Star Wars Adventure Journal, a magazine published by West End Games. "Mist Encounter" told of how a castaway Thrawn (who gave his full name as Mitth'raw'nuruodo, a word unpronounceable by humans) was first found by Voss Parck of the Imperial Navy, who was so impressed by Thrawn's ability to single-handedly fight off encroaching Imperial Forces that he recruited him once he was finally captured. "Command Decision", which, from what I could find, is no longer in print, told of Thrawn's early explorations for the Empire into the Unknown Regions. "Side Job" was a novella co-written by Zahn and X-Wing series author Michael A. Stackpole, published in four parts and later re-published in the anthology Tales from the Empire. It told the story of the mission that earned Thrawn the command of the Noghri from Darth Vader, as well as serving as an early adventure of X-Wing mainstay Corran Horn. This was the start of a collaborative partnership between Zahn and Stackpole, who would often write stories about each other's Star Wars characters.

Thrawn also made a major appearance in the 1994 video game Star Wars: TIE Fighter, in which was told the story of how he became a Grand Admiral, by leading forces against the traitorous Grand Admiral Zaarin, who sought to overthow Emperor Palpatine with a force of advanced TIE fighters. I haven't played the game but it's apparently still available for download today.

The commercial success of the Thrawn Trilogy meant that those books were used as a pattern for many books that followed. The return/rise of some Imperial warlord, the discovery of heretofore hidden Imperial technology or weapons, and/or someone wanting to kidnap Han and Leia's children were factors in much of the Star Wars media released through the '90s. Star Wars was back, but it seemed, again, to be stuck in place. The war with the Empire dragged on and on, through book after comic, with no end in sight. Then, stirrings began to come from George Lucas himself, who seemed primed to finally return personally to the franchise, with the missing first three episodes. This could mean the end of this golden age of Star Wars books, as the new films drew attention away from the years after Endor. Somehow, the galactic civil war needed to be resolved before then. Zahn would return, to see the end to the era he started.

Covers for the Hand of Thrawn Duology | Art by Drew Struzan

The Hand of Thrawn [1997 - 1998]

The Hand of Thrawn duology was Timothy Zahn's reappearance in Star Wars novels, and it serves as a more-or-less direct sequel to the Thrawn Trilogy. That is, it was the more immediate sequel to The New Rebellion by Kristine Kathryn Rusch, which had come out the year prior. (That book had been about a revolt against the New Republic led by two of Luke Skywalker's former students. If you're worried that Zahn's books were thus about Luke going into exile and taking up spearfishing, don't. This is Legends Luke Skywalker; it's not the first time his students have gone on a genocidal rampage, and it won't be the last. He doesn't care.) But, while Zahn's stories and characters have been drawn from by many of the authors to come to Star Wars after him, he doesn't generally draw back from their stories. Luke's various Jedi students do not appear in these books. The Hapans, a people first introduced in The Courtship of Princess Leia that would play a significant role in Star Wars books going forward, do not appear. Lando's wife, Tendra, whom he had married in the intervening ten years since the events of The Last Command, does not make a major appearance, even though Lando does. Only Corran Horn and Booster Terrick, two characters created by Michael Stackpole, are brought in from other works. The characters are mostly the same characters as were in the Thrawn trilogy, which is what I mean when I say this is a sequel to that. This is a story about Talon Karrde, Borsk Fey'lya, Gilad Pellaeon, Mara Jade, and, even though he'd been dead for a decade, Thrawn.

The duology presents Thrawn as the Empire's last hope, without whom they have no chance of victory. The first book, Specter of the Past, opens with Gilad Pellaeon, who by now is the Supreme Commander of what remains of the Imperial military, proposing to the Moff's Council that the Empire should sue for peace with the New Republic. When he leaves for a conference with Leia Organa Solo to begin peace talks, a corrupt moff and a former Imperial guardsman hatch a plot to keep the war going. They enlist the aid of a con artist to impersonate Thrawn, saying the Grand Admiral had faked his own death and had lain in hiding, waiting for the New Republic to begin to collapse under that weight of ruling the galaxy. That collapse appears to start with the start of incomplete Imperial records implicating Bothans in the Empire's destruction of the beloved Caamassi people. An actual roster of which Bothans were involved is not included, but this may exist in a more complete document. The New Republic becomes bitterly divided over whether the Bothan people deserve collective punishment for concealing the matter, which the Bothan leaders had been privately investigating. Some even suggested that all Bothans were guilty by association of the Caamas sabotage itself. The corrupt Moff seizes on the controversy, deploying agents to work as agitators, hoping to split apart the New Republic's multi-species coalition.

Nowadays, you wouldn't see this in Star Wars, at least not in this way. The assertion that all Bothans shouldn't be held responsible for the actions of a few Bothans is undercut by way the non-human species all act in one mind for the whole controversy. More recent stories, both in Star Wars and in space-set fiction generally, have tried to bring more individuality to members of alien species than was necessarily present in the past. I think that part of the reason for that might be that there are parallels to draw between drawing strict divisions between fictional species and drawing strict divisions between actual people groups in ways most authors don't endorse and thus don't want to appear to endorse by metaphor. No one wants to make the next Bright. But also using a character's species as a shorthand (Weequay pirates, Duros pilots, Bith musicians) is kind of lazy writing, and it's just not very interesting after the first few times. Granted, it's not unreasonable to say that members of different species, having different homeworlds and having grown up in different cultures, and even having different biologies with different sensory abilities and different physical needs, might be much more similar to each other than to members of other species. But even still, there should be some individuality to each character. In Star Wars, we have the clone troopers, who are literally the same person copied over and over again, and yet they are characterized differently enough for the audience to be able to tell them apart and have favorites. The same is not true of, say, the Noghri, especially in the Hand of Thrawn books.

I think that, more than anything, the flatness of Zahn's aliens is due to the fact that Zahn doesn't write many non-human perspective characters. This is not unique to Zahn, particularly in the '90s. Indeed, even in the films out at the time, the only non-Human, non-droid character with lines in English was Admiral Ackbar.

Anyway, the Caamas Document Crisis is only half of the duology's story. The other half is related, at the beginning, before becoming about Thrawn, the real Thrawn. Talon Karrde remembers how his old boss, Jorj Car'das, was an obsessive data hoarder and hopes that he might have an intact copy of the Caamas Document. He goes off in search of Car'das, finds him, and learns that he doesn't have it, but does have documentation that the rumored return of Thrawn is all a sham. Karrde passes this on to Pellaeon, and that's the end of that little caper. But Karrde had also sent Mara Jade looking for Car'das, and what she found instead was Thrawn's secret base from which he had charted the Unknown Regions for Palpatine. She, along with Luke Skywalker (who had a vision that she was in trouble and thus came running) find the base still staffed by Admiral Parck and Imperial troops, along with a few of Thrawn's people, the Chiss. They've been there building "The Empire of the Hand", an offshoot of the main Empire comprised of Thrawn's hand-picked devotees. They capture Luke and Mara, who learn that Thrawn had left instructions that, if they ever heard news of his death, they should wait ten years, then look for his return. Now that it appears Thrawn has returned, Parck intends to reach out to the Imperial Remnant, offering them the vast tracts of territory they've mapped. Luke and Mara escape, and on their way, they find a basement lab with an almost-matured clone of Thrawn in a tank, which appears to have been the real ten-year plan. In the process of fighting their way out of the base, Luke and Mara wind up flooding the lab. The clone, despite being submerged in a tank, drowns in the floodwaters, a messiah thwarted.

The Hand of Thrawn duology is not the beloved classic that the Thrawn trilogy is. The story of the two books is a bit convoluted and drawn out, and there aren't the sort of grand battles the trilogy had. It's all well thought out and put together, very clever, but not especially engaging. When it is remembered, it's for the changes it made to the Star Wars status quo. These were the books that ended with peace made with the Empire. These were the books that ended with Mara Jade agreeing to marry Luke Skywalker. These were the books that ended with Booster Terrick's Star Destroyer getting painted red. But most importantly for us today, these books were the first to hint that Thrawn had his own agenda beyond loyalty to the Empire, an idea Zahn would expand on in his next works...

Covers for Survivor's Quest, Outbound Flight, and Choices of One | Art by Steven D. Anderson, Dave Seeley, and Daryl Mandryk

Thrawn in the New Millennium [2005 - 2011]

The turn of the 21st Century saw two big projects for Star Wars. First was the return to the screen with the Prequels. But at the same time came The New Jedi Order, a massive publishing initiative that told the story of a new war against the Yuuzhan Vong, a fearsome extragalactic race of fleshcrafters whose invasion of the galaxy serves as the first major trial of the next generation of Jedi Knights. Running from 1999 to 2003, the project was the big Star Wars debut for Del Rey, a sci-fi imprint (also owned by Random House) which took over from Bantam Spectra and which still publishes Star Wars books today. (CORRECTION: The Del Rey imprint had, in fact, published pre-Thrawn trilogy Star Wars books such as film novelizations and Alan Dean Foster's Splinter of the Mind's Eye, which was based on an unused film treatment. Thus NJO was not a debut strictly but was the start of a new publishing era.) The series featured twenty-two books by thirteen authors, including the first Star Wars books from franchise mainstays Matthew W. Stover, Troy Denning, and James Luceno, and the last from Michael A. Stackpole.

Timothy Zahn did not participate in The New Jedi Order; as I mentioned, he generally keeps to himself when writing Star Wars. But both The New Jedi Order and the Prequels had a great influence on his next project. After years of allusions and hints, it was finally time to tell the story of Outbound Flight.

The first mention of Outbound Flight came all the way back in Heir to the Empire, as part of the backstory of Joruus C'baoth, the Thrawn trilogy's less-beloved secondary villain. He was the mad clone of Jedi Master Jorus C'baoth, who led an expedition into the Unknown Regions which Thrawn tells Pellaeon he had destroyed at the behest of the Emperor. Zahn couldn't give much more detail than that, since George Lucas had forbidden any stories being set during or just before the Clone Wars before he could tell his own tales in the Prequels. But, by 2005, the Prequels had been released, and Zahn was finally free to tell his story.

I'm not sure how much the story of Outbound Flight changed between 1991 and 2005. I'm sure it changed some, given how different the Clone Wars were shown to be in the Prequels compared to how they were described in passing in Zahn's earlier books. One thing I do know was an influence on Zahn was the Lucas films' strange release order. Zahn wrote of Outbound Flight in two books. The first, Survivor's Quest, was released in 2005. Del Rey had approached Zahn with a request that he write a book about Luke and Mara that could parallel Tatooine Ghost, a contemporaneous book focused on Han and Leia. Zahn decided to write about Luke and Mara traveling to Chiss space to examine the newly-found wreckage of Outbound Flight. Then, in 2006, the second book, simply titled Outbound Flight, would tell the story of how the mission came to be wrecked in Chiss Space, and how Thrawn first met Darth Sidious. Like Lucas's two trilogies, the earlier story was saved for last.

I won't say much about Survivor's Quest, as it only occasionally mentioned Thrawn himself. What we do learn about him is what we learn of the Chiss Ascendancy, which first properly appears here. This was the society which Thrawn came out of, which he was thrown out of, actually. We learn in this book that his people as a whole considered him a renegade, a dangerous subversive who rejected cautious Chiss ethics for bold, preemptive military actions. Zahn also suggests, more forcefully than he had before, that Thrawn's allegiance to the Empire was part of a plan to fortify the Galaxy against threats from beyond.

And now we get to Outbound Flight. This was the first book of Zahn's that I read, actually. My initial assessment of it was that I liked it, but that it seemed weird for Star Wars. I'd stick with that assessment today, really. Outbound Flight works as a real turning point in Zahn's work in Star Wars, as it, and the books Zahn has written for the franchise since, aren't your standard hero vs. villain tales. You aren't wholly cheering any of the main characters in Outbound Flight on.

Jorus C'baoth is the best part of the book. While his clone got upstaged in the Thrawn Trilogy, C'baoth here is an equal presence with Thrawn. He's probably the most evil Jedi we ever saw until Pong Krell came along, and even Krell wound up as a turncoat. C'baoth is committed to the Jedi cause, in his way; his downfall comes from his arrogance and obsessiveness. His story, along with that of his former Padawan Lorana Jinzler, is very well told, and very tragic.

Thrawn appears in Outbound Flight as the young Commander Mitth'raw'nuruodo of the Chiss Expansionary Fleet, the part of the Chiss military responsible for scouting beyond the Ascendancy's borders in search of possible threats. While on such an excursion, he finds a trio of Corellian smugglers, including a young Jorj Car'das, trying to escape an angry Hutt by fleeing into the Unknown Regions. He recruits the smugglers into a convoluted plan to bait out a society of nomadic pirates and slavers known as the Vaagari, promising the Corellians a share of seized Vaagari plunder in return for their aid in identifying and cataloging it. From there, he sets Car'das up as an unwitting agent in his plot to destroy the Vaagari, something he must do in accordance with Chiss laws against preemptive strikes.

Thrawn's portrayal in Outbound Flight has attracted a lot of criticism. As he was created, as a villain, his incredible competence made him a more terrifying threat, but as a protagonist, it becomes a liability. While he was always a brilliant strategist in earlier portrayals, his actions in this book make him seem almost omniscient. And that's when he's actually commanding in a naval battle. For much of the first half of the book, Thrawn and the Correlians simply dig through a cache of Vaagari-captured artifacts and swap language lessons. Thrawn quickly picks up Galactic Basic, while the Correlians struggle with Cheunh (the Chiss tongue), which Humans are apparently physically incapable of pronouncing correctly. Thrawn is able to describe peoples he's never seen or heard of with uncanny accuracy based solely on observing pieces of their art from the Vaagari cache. How he is able to do this, what characteristics of the artworks are giving him clues, is left unstated. On top of all this, Thrawn was apparently quite the charmer in his younger days. Maris Ferasi, another of the Correlians, develops a crush on the misunderstood, art-loving commander, which makes Dubrak Quento, the leader of the three Correlians, quite jealous. Altogether, Thrawn seemed a bit too perfect (and too Byronic, weirdly) for many people's taste. Where Lucas's prequels had been, perhaps, a bit too cool, Zahn's was a bit too clever.

The other main criticism of Outbound Flight has to do with who Thrawn came into conflict with C'baoth in the first place. Basically, Darth Sidious had sent a task force ahead of Outbound Flight to destroy C'baoth and the other Jedi coming along with him as soon as they passed out of known space. Thrawn finds this force while on patrol and neutralizes them. Unable to destroy Outbound Flight himself, Sidious's agent, Kinman Doriana, decides to get Thrawn to do it. He arranges a call between Thrawn and Sidious, who tells Thrawn that the galaxy has been under surveillance by the "Far Outsiders", that is, the Yuuzhan Vong, who have already captured at least one Jedi and who could gain considerable knowledge about the Galaxy were they to capture Outbound Flight. They would then use that knowledge to destroy the Galaxy, the Chiss Ascendancy included. Thrawn acknowledges that the Chiss are already aware of the Far Outsiders, and pledges to turn Outbound Flight back toward the Republic or else see to its destruction.

As we've seen, Thrawn supporting the Empire because he believed the Galaxy needed to be united against external threats was not a totally new idea, and when the Vong were introduced, they fit naturally into place in Thrawn's story. That wasn't the issue; the issue was that now it was suggested that Palpatine himself just wanted to protect the Galaxy from invasion. And Palpatine just isn't the kind of villain that needs much rationalizing. He's an evil wizard. He knows he's an evil wizard. Why act like he's doing what he's doing out of the goodness of his heart?

Well, I don't read it like that. Darth Sidious is a tempter, always making promises, some empty and some not, that those who serve him can achieve their greatest desire. He promised Dooku an end to the stagnation of the Republic; he promised Vader the power to save his loved ones; here, he promises Thrawn the chance to defend his people. Throughout Outbound Flight, we see how defending his people, even by means they wouldn't approve of, is Thrawn's purpose in life, and so we come to understand why he would ally with Sidious. That part of the book works.

Following the Outbound Flight books, Zahn's next work for Star Wars was the Hand of Judgement duology (Zahn does love his hands, doesn't he?). These books, Allegiance and Choices of One, are set between A New Hope and The Empire Strikes Back, and they tell of Mara Jade during her time as the Emperor's Hand, as well as of a squad of stormtroopers who desert after being ordered to fire on civilians; think Finn, but there are five of them and they don't quite join the main fight against the Empire. These stormtroopers wander the galaxy in a ship full of stolen military equipment, calling themselves the "Hand of Judgement" and fighting against corrupt Imperial officials in a quixotic attempt to make the Empire live up to its stated ideals.

Thrawn appears in the second book, playing a game of military puzzles against Nuso Esva, equally brilliant Outer Rim warlord who has been manipulating Imperials and Rebels alike in a bid to expand his own territory. At the end of the book, he captures the Hand of Judgement, but rather than punish them, he sends them to his base in the Unknown Regions, to be the first of the stormtroopers of the Empire of the Hand. (See, we have the Emperor's Hand, the Hand of Judgement, and the Empire of the Hand all in the same book.) Thrawn says that will actually be the great unifying force for justice and order that Palpatine's Empire only claims to be.

This is the last we saw of the Thrawn we first met in Heir to the Empire, the Thrawn of Legends. We'll get to Canon Thrawn in a moment, but first I'd like to examine the question Legends Thrawn raises: could there be a good Empire? What if Palpatine and Tarkin and Vader and Isard weren't running things. What if there were no Death Star destroying planets or Dark Lords choking the life out of people. Such an Empire would clearly be better, but would it be a good thing? More specifically, would Thrawn's idealized Empire be good?

I would say no, even that wouldn't be a positive good. Take the Empire. Take the sadists, who were only onboard to inflict suffering on others, out. Take the narcissists, who generally hate the galaxy and the people in it, who don't see themselves as doing anything worse than they believe anyone might do, out. Take the New Order die-hards, whose anger at the Separatist movement and the Jedi and anyone else who would question Imperial rule formed a lot of the anti-alien and generally anti-democratic sentiments throughout the Empire, and take them out. Once you've taken all those actively malignant elements out, the only people you'll have left willing to hold an Empire together are the people like Thrawn, who feel pressed to bring the Galaxy under strong central rule out of fear that a divided Galaxy will inevitably become a defeated Galaxy, either defeated by the Vong or someone else. That fear quickly becomes an all-purpose excuse for all manners of evil. Sure Alderaan was destroyed, but won't the Vong destroy more worlds if the Alderaanian leadership compromises Imperial rule? Sure, many species might be enslaved to build the war machine, but if the Vong aren't kept out, they'll enslave all species, probably turning them into horrid mutants to boot. Sure, the Noghri were duped into the fight, but you could hardly expect such a recently contacted people to grasp the threat posed by the Vong; you need to enlist their much-needed aid on terms they'll understand. You're saving Honoghr, really, from the Vong. And so on and so on. Fear is compromising that way. It gets people to stop considering the right and wrong of their actions, to just act rapidly in their interests. While fear of what's in front of you can be clarifying, fear of what may be can blind. Thrawn could not lead a good Empire, because he could barely see for himself what good was.

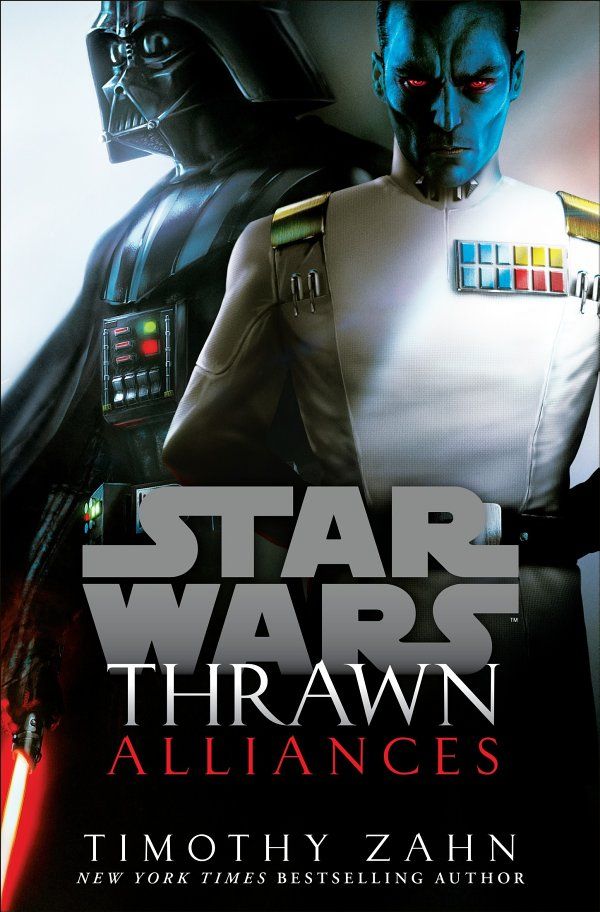

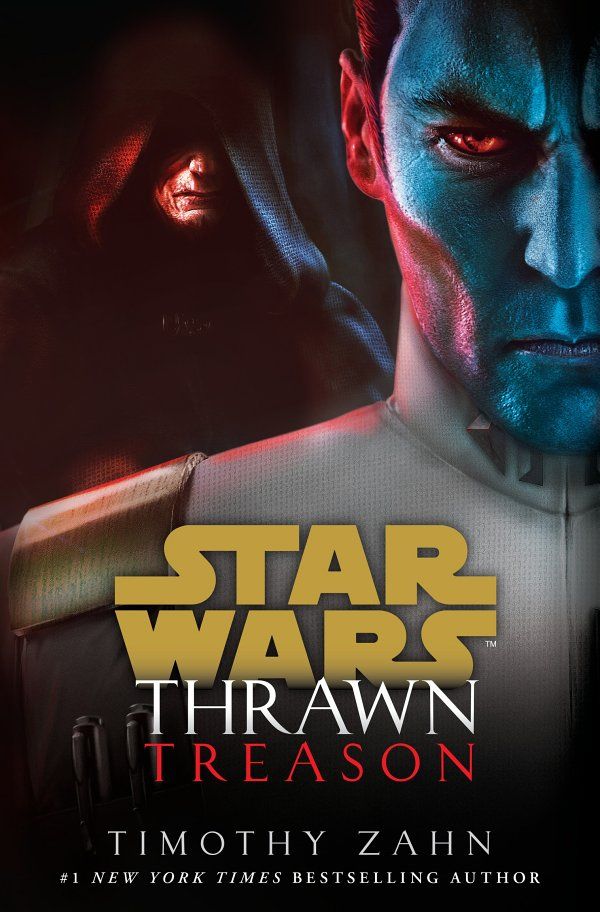

Covers for the Canon Thrawn Trilogy | Art by Two Dots

New Canon, Same Great Thrawn! [2016 - 2019]

Zahn followed Choices of One with Scoundrels, a sort of Oceans 11 story starring Han and Lando, and not featuring Thrawn at all. Whatever further plans he had for Thrawn seemed to be dashed when Disney bought Lucasfilm and declared the establishment of a new Star Wars Canon.

I'd mentioned the conflict that arose between how Zahn described the Clone Wars and the way Lucas later described it in the Prequels. And, if you've read my review of The Mandalorian's first season, you're familiar with the much more thorough invalidation of Karen Traviss's Republic Commando books. These were not unique situations. Lucas was happy to share his world with other writers, but he never was one to really care what they wrote when it came time to tell his own story. He was able to get away with that because he was George Lucas and what George Lucas said happened in Star Wars in what happened in Star Wars. The new execs under Disney didn't have the same creative mandate. Hence, the Canon. The six existing films and the Dave Filoni-helmed Clone Wars television series were declared Canon, which meant that whatever new Star Wars stories Disney put out would have to respect them and couldn't flagrantly contradict them. All such new stories, be they books, comics, films, games, TV shows, VR experiences, or whatever would likewise be Canon, and a panel of writers would be on staff to help keep works in line with each other as they were being created. As for the old EU, including all of Zahn's work, these were not Canon. If writers wanted to, they could use the old EU, now called "Legends", as reference material if they wanted, but many creators instead took full advantage of the newly clean slate. When the first details emerged about the upcoming seventh episode of the film franchise, it was clear that Heir to the Empire was not going to be a part of the Star Wars story going forward.

Once Disney got the rights to Star Wars, they didn't just want their own new movies. They also wanted something like what Cartoon Network had had in the five-season Clone Wars series. Dave Filoni and some others from that show were tapped for a similar project, Rebels, to air on Disney XD. It told the story of a small team of freedom fighters from the world of Lothal, in the period a few years into the Empire's reign, with each new season giving their fight a greater scale as they become more integrated into the Galaxy-wide Rebel Alliance. For the first two seasons, the main villains were the Jedi-hunting Inquisitors, and, eventually, Darth Vader himself. They were chiefly concerned with killing former padawan Kanan Jarrus and his student, Ezra Bridger, two members of the Rebels central cast. In Season 3, however, the Rebels were set to become a military threat, and the series would need a military villain. Answering fan demand, Disney announced that Season 3 would feature Grand Admiral Thrawn. What's more, Timothy Zahn was returning to Star Wars with a new trilogy of books, also featuring Thrawn.

NOTE: By this point in time, The Edwards Edition existed, which means that I've already reviewed, in full, each book we have left to cover. Therefore I won't be going as in-depth about the overall stories outside of Thrawn's storylines.

One thing I will say is that the new Thrawn Trilogy isn't really a trilogy so much as it is three different stories featuring the same characters. The first of the three, titled simply Thrawn, is an origin story, starting with a retelling of "Mist Encounter" and following Thrawn as he climbs through the ranks of the Imperial Navy, ending with him being made a Grand Admiral and assigned to the Lothal sector to root out the Rebel group there. The second two books detailed later missions which took Thrawn away from Lothal at certain times.

There are a few obvious differences between the new Thrawn Trilogy and the old. For one, the new trilogy is a tie-in, written to expand the main story being told on Rebels. (This was true of a lot of the early Canon books, actually. They tended to be tie-ins to something on-screen moreso than their own things.) For another, Zahn actually began to write scenes from Thrawn's perspective. And, of course, the time frame is different; Canon Thrawn is not the last hope of the Empire. He is the finest officer of their navy at its peak. He, moreso than the Legends version, functions as a detective. His primary function is investigative, in all three books and in Rebels.

For his part, Zahn seemed unperturbed by the shift from the Expanded Universe to Canon. even as several of his other characters, such as Mara Jade and Garm Bel Iblis, seem unlikely to follow Thrawn into the new timeline. Zahn has stated in interviews that Thrawn is the same character that he ever was, even if the stories he plays a part in are all different. I'd say that this is mostly true. Canon Thrawn is already a Grand Admiral at the time when Legends Thrawn was still just a captain. He's also taken on Grand Admiral Zaarin's role spearheading the TIE Defender program. The biggest change is that there's no Empire of the Hand in Canon. Instead, we have Thrawn acting as a sort of double agent for the Empire and the Chiss Ascendancy (his exile in Canon is staged, where it seemed genuine in Legends), and he's secretly sending the Empire's best and brightest back to his home. The Vong—well, the Vong are actually a bit up in the air, but they haven't officially appeared in Canon, at least not yet, but there are still some groups beyond the known Galaxy, and Thrawn is trying to position the Empire and the Ascendancy such that one can be sacrificed to save the other. Which one he'll sacrifice is a point of great tension in Canon Thrawn books.

So, while I've already covered Zahn's Rebels tie-in trilogy, I haven't spoken about Thrawn in Rebels itself yet. This wasn't the first Thrawn story not to come from Zahn's hand; besides TIE Fighter, he was featured in a few other video games, as well as appearing in a volume of the Goosebumps-like Galaxy of Fear series. But this was the most prominent example of non-Zahn Thrawn to date. Thrawn fans were tuning in to the Season 3 premiere, eager to see the Grand Admiral in action.

They were not disappointed. Thrawn was portrayed by the Danish actor Lars Mikkelsen, whose odd European accent and quiet, almost murmuring delivery gave Thrawn's voice, which Zahn would only ever describe as "coolly modulated", a defined character. Indeed, as I read back through Zahn's books as I wrote this piece, it was Mikkelsen's voice in my head as I read Thrawn's lines. Following Darth Vader, who had made a terrifying appearance in the Season 2 finale, was no easy feat. Wisely, the show didn't have Thrawn do much right away. Instead, as the season played out, Thrawn kept mostly in the background. Watching. Listening. Thinking. That's what made him such a threat; he wasn't an idiot. He wasn't fooled by the Ghost crew's ploys, though he lets them get away in hopes of producing the perfect opportunity to destroy the greater Rebel force.

Season 3 particularly has some fantastic tension to it, as the audience knows that Thrawn is waiting to spring a trap. Thrawn is defeated, of course; Rebels isn't the sort of show to have the heroes lose in the end. But both of his defeats come from well outside anything he could anticipate. The key to defeating Thrawn, we see, is not subterfuge or military strength, both of which Thrawn can answer overwhelmingly, but reliance on the Force, which he knows little of. Altogether, Thrawn in Rebels was a faithful adaptation, and a return to the villain role I still think Thrawn works best in.

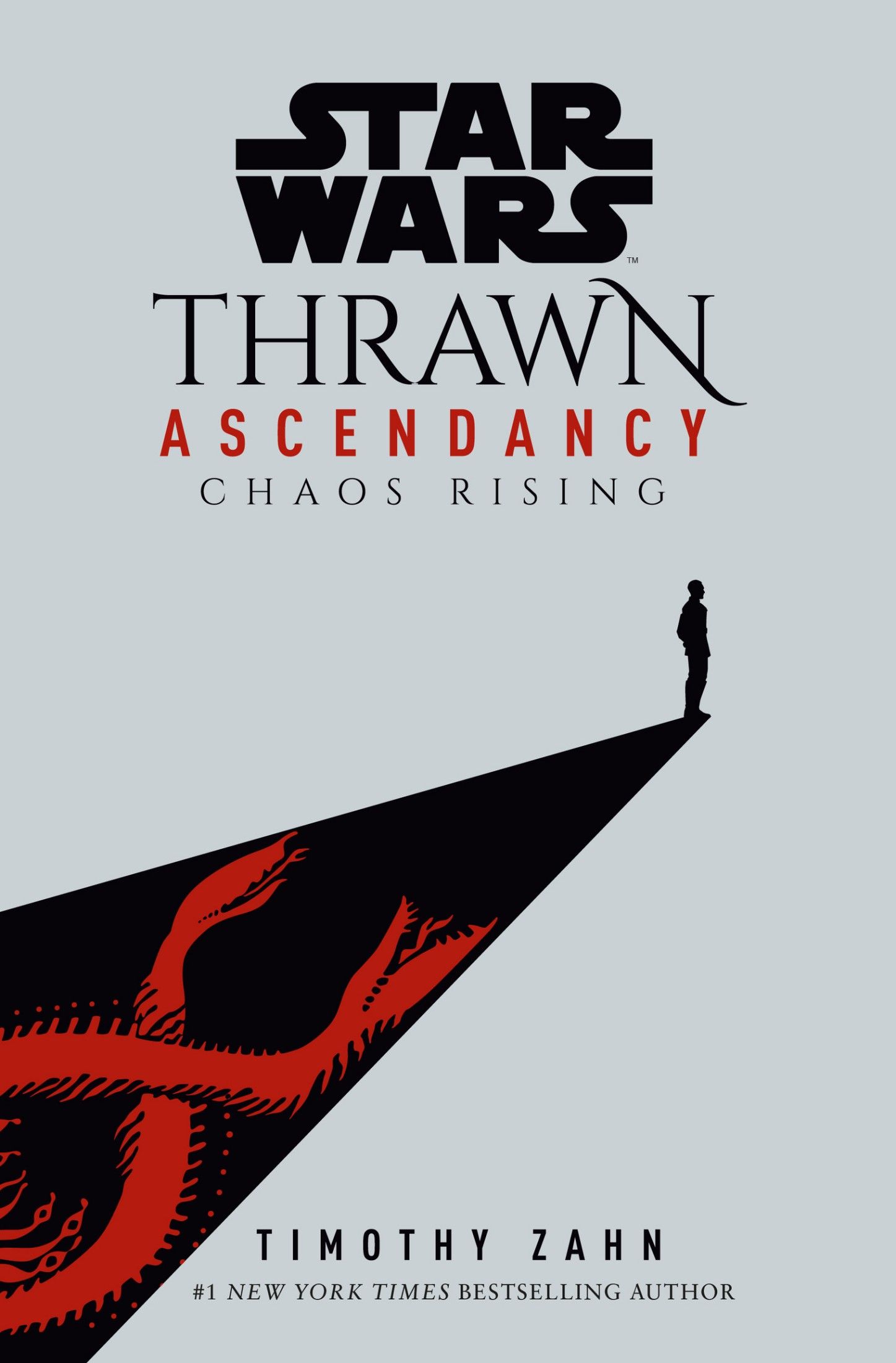

Covers for the Thrawn Ascendancy Trilogy | Art by Sarofsky

Thrawn's Past, and Our Present [2020 - 2021]

While he was telling Thrawn's story in his new trilogy, Zahn was also telling more about the Chiss: their society, their place at the edge of the Galaxy, and their relationship with the Force. It was thus welcome news when it was announced that Zahn would be following up the new Thrawn trilogy with another trilogy, this one set in the Chiss Ascendancy toward the end of the Clone Wars era. The first volume, Chaos Rising, was published in September of 2020. The second, Greater Good, was published mere days before this piece, at the end of April 2021. The third book, Lesser Evil, is due out this November.

I obviously can only comment on how the Ascendancy Trilogy begins at this point. In a lot of ways, the Thrawn of Chaos Rising is a further revised version of the Thrawn of Outbound Flight. He's still a brilliant strategist, and he still has admirers because of that, but he isn't near-universally beloved by everyone he encounters, and those who dislike or mistrust him have valid reasons to; they aren't simply jealous of his ability. The book is helped greatly by the main-character presence of Ar'alani, Thrawn's superior and life-long friend who has the best understanding and most balanced appraisal of him out of any of Zahn's characters.

That said, the Ascendancy Trilogy has featured Thrawn as a character, not the character, or even the most interesting character. The next books might focus more on him again, but Chaos Rising was at its best when telling of the other Chiss. They're the new characters, the people we can still learn about, who Zahn can still write new things about, who haven't been around for decades.

The Future of Thrawn [2021 -

So that's Thrawn, and all thirty years of the stories that have featured him so far. Are there another thirty to come? It's hard to say. He still has fans, especially where it counts, within Lucasfilm. His name was dropped in the most recent season of The Mandalorian, in an episode featuring Clone Wars and Rebels hero Ahsoka Tano during her search for Ezra Bridger, who disappeared along with Thrawn into hyperspace at the end of Rebels. It has long been promised that the search for Bridger would be told in some form, and that form appears to be the upcoming Ahsoka streaming series. It seems very likely that the series will feature Thrawn's live-action debut. What he'll be doing I can really only blindly guess at. Thrawn is an unpredictable character, nuanced, multidimensional, and very, very clever. You can't guess what he might do next, which is the appeal of the character. Whether he's rebuilding the Empire or rooting out the early Rebellion, inspiring his troops or distressing his superiors, commanding vast fleets or lost in deep space, you can't know how his story will play out until you've experienced it. So you keep reading, keep watching, as Star Wars fans have done for thirty years, and counting.

Member Commentary