Running Commentary 9/11/2023

Hello,

I have not seen a northern pintail in the past week. I did see a cormorant and a kingfisher at a lake, but that's as much as I've seen of waterfowl. I'm planning a trip this coming weekend to see, hopefully, a least bittern, and I may see a pintail there. I'll keep you posted.

Anyway...

Watching...

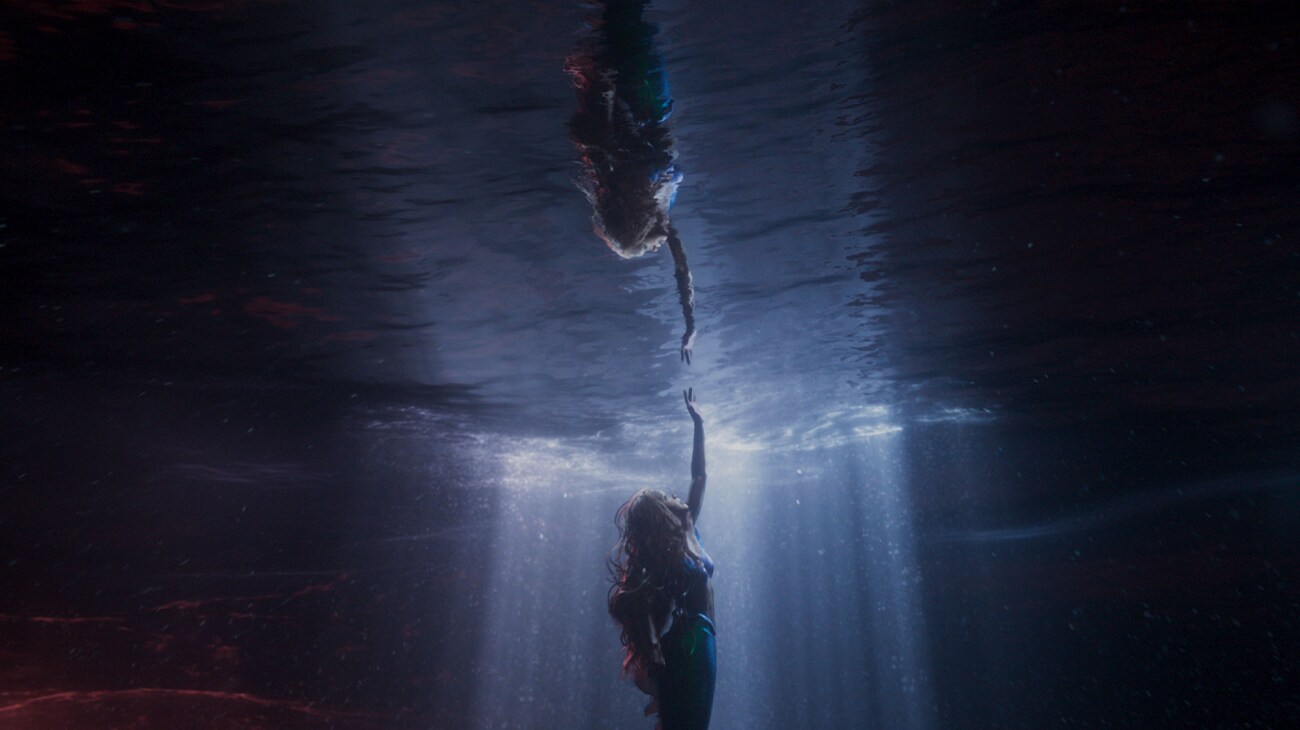

The Little Mermaid (2023)

So I wasn't really planning to watch the Little Mermaid remake but since I have Disney+ I sometimes get asked to show things to other people, so I did wind up seeing this. And I'm actually kind of glad I did. Disney's original The Little Mermaid didn't really need a remake; it's still quite good. But the new one is also quite good, in some ways surpassing the original. It's an hour longer, and it fills much of that hour better exploring Eric's character, actually. The film-makers cleverly made him a sort of mirror of Ariel: where she has her collection of artifacts from the surface, he has a collection of his own that he's dredged up from the bottom of the sea; where she dreams of being part of the human world, he yearns to travel to uncharted waters. When they come together, it feels like two people meeting in the middle, on the beach, I suppose, rather than like Ariel simply leaving the ocean.

The animation is, in its way, about as good as the original's. The underwater scenes are convincingly done, with lots of beautiful, swirling sea life. As for the animated characters, Flounder looks weird, but Sebastian looks fine and Scuttle was surprisingly expressive for a gannet. Daveed Diggs and Awkwafina give very expressive vocal performances that shine through their characters' stiff-plated faces. Also, everyone who's given a song to sing can actually sing really well, which hasn't always been the case with these Disney live-action remakes. Overall, I think I'd show a little kid the original, since the remake is two-and-a-half hours long, but this new one had a lot of work put into it, and that work paid off. If you're a Little Mermaid fan who hasn't seen the remake yet, I'd give it a watch.

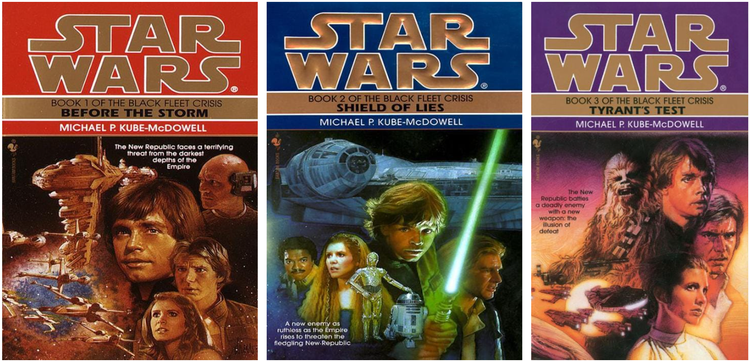

Ahsoka

We're midway through the season now, and things are really starting to move fast, story-wise. (And literally, in the case of the Eye of Sion). Here are my notes on Chapter 4:

- Marrok died, although it looks like maybe he died a while ago. If he was, as was indicated, a nightsister-reanimated corpse, that would do a lot to explain both why there's an inquisitor still around at this time, and why Marrok didn't show up until after Baylan and Shin had rescued Morgan Elsbeth.

- Speaking of learning things, Baylan mentions that Sabine has no family left, which would indicate that Clan Wren was otherwise wiped out in Moff Gideon's conquest of Mandalore. That would explain why they didn't join Bo-Katan in retaking it.

- Baylan got that time to shine I was hoping he'd get in this episode. He and Shin really are interesting characters, moreso than I was expecting them to be. I noticed he didn't initiate the duel with Ahsoka, and he doesn't initiate a fight with Sabine. It seems that he lost faith in the Order but didn't wholly abandon Jedi ways. It's clear that he has a degree of faith in Thrawn, and isn't simply a mercenary collecting his pay. I think it's pretty likely that we'll get a novel focused on Baylan and Shin sometime in the near future.

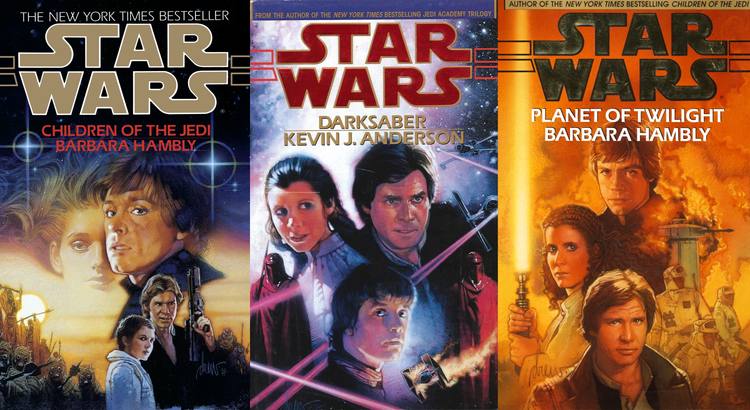

- Sabine agreeing to give the map to Baylan for the chance to be reunited with Ezra was the wrong call but was understandable. I wonder if having one of our heroes join morgan's quest for Thrawn might be a way the show means to explore Thrawn's place as Star Wars's "noble villain". In Zahn's Thrawn trilogy, none of the heroes ever interacted with Thrawn directly, but since then he's been fleshed out into a character who's a lot less overtly evil that most Star Wars villains, the sort who could convince a good, naive person to follow him. We've never seen that happen, though.

- So, I was right that Hera was going to try to rescue Ahsoka and Sabine, but wrong that she'd take Zeb along. She did bring Carson Teva, who was deployed with Zeb in the Outer Rim. Anyway, she also brought Jacen, for some reason.

- I don't think Ahsoka is dead, since the World Between Worlds is not the afterlife. As to how she got there from falling off a cliff, I could only speculate. We'll surely get some sort of answer in the next episode.

- Digital de-aging somehow just doesn't work on Hayden Christensen. It didn't in Obi-Wan Kenobi, and it doesn't work here. It just makes him look odd.

- I expect the next episode will largely feature Ahsoka in the WBW, with Sabine, Morgan, and company arriving in the other galaxy and finally meeting Thrawn.

Bird of the Week

Somehow, I've never featured a bird from New Zealand in this space before. After years of writing Bird of the Week, that's somewhat inexcusable. New Zealand is the realm of birds; they are the dominant form of animal life there. No mammals (besides a few bats and a long-extinct mouse-like creature) are native to New Zealand. The first large mammals to set foot on New Zealand were the Māori, a Polynesian people who first arrived on the islands less than a thousand years ago.1 The Māori found the islands to be full of strange birds, the most fearsome of which they named "moa" (or possibly "te kura").2 These were enormous ratites, like ostriches but twice as tall as a man. They seem to have been plant-eaters, their role in New Zealand's ecosystem being roughly analogous to that held by deer in North America. The Māori hunted the moa to extinction within a century of their arrival in numbers.3 (The Haast's eagle, which is estimated to have been the largest raptor ever to fly Earth's skies at a weight of over thirty pounds, also went extinct at this time, as it depended on the moa for food.)4

Europeans, particularly the British, eventually got around to colonizing New Zealand in the 1800s, after having made at least a go at colonizing the rest of the world. They were even harder on the native wildlife than the Māori had been (and pretty hard on the Māori themselves). The Māori had brought dogs and rats with them2, and the British brought cats, weasels, and more rats from home, along with possums from nearby Australia; all these predators wreaked havoc on unsuspecting birds.5 The British were also more effective at clearing the island's forests to make way for human settlement and farming. All this background brings us to this week's bird: the Kākāpō.

Kākāpōs lived throughout New Zealand. Like the moas, the kākāpō was hunted by the Māori, and by the Haast's eagle before them. It was usually pretty good at evading the eagle and other birds-0f-prey. Kākāpōs are nocturnal, they look like mossy logs from above, and when they sense danger, they freeze. A predator flying over a darkened forest would be unlikely to spot a kākāpō. But a Māori hunter or his faithful hound would easily spot a bird just standing there, still. They'd also be tipped off by the bird's strong, unique smell, which kākāpōs use to find each other in the dark. The British were less interested in hunting the kākāpō, but, again, they cleared a lot of forests. The kākāpō's population collapsed with the falling trees. Those introduced mammal predators started to pick off those who were left. By the end of the 20th Century, there were only a matter of dozens left, mostly confined to small islands in the "Fiordlands" off the South Island, which were still without mammals.6,7,8

This decline is a shame, not just because human activity driving other species to extinction is always a shame. The kākāpō is probably the most lovable of all birds. They are parrots, but they are very strange parrots. They cannot fly, instead, they jog through the forests in an especially frolicsome manner. and climbing trees using their clawed feet and beaks. Their faces are round, fluffy, and more human-like than that of most birds. They are about the size of a small dog. Overall, they look more like a stuffed animal than a real one. The kākāpō has become a classic example of what conservationists call "charismatic megafauna": likeable, usually large creatures that become mascots of sorts for their habitats. Recovery efforts for such species are the beneficiary of much attention and financing from people eager to save a favorite animal. Intense wildlife management of the kākāpō has been successful in reducing its decline. Now there are over 200 kākāpōs9, and this past July 4 males were reintroduced to the North Island mainland for the first time in decades, in a project part of a broader initiative to eliminate non-native mammal predators (besides people, who have thus far been able to be reasoned with regarding not killing kākāpōs) and restore the islands as the realm of birds once again by 2050.10,11

The name "kākāpō" is a combination of the Māori "kākā", meaning "parrot", and "pō", a suffix meaning "night" or "nocturnal". (This is not to be confused with the similar-sounding "cockapoo", a combination of the words "cocker" and "poodle" that is the name of a dog which is a combination of a cocker spaniel and a poodle.) George Robert Gray, the English naturalist who first described the species to science, called it Strigops habroptilus, Greek for a "soft-feathered, owl-countenanced thing". Scientists today still use the name, though it's been changed to the more grammatical Strigops habroptila. Gray never went to New Zealand, and only knew that the specimen he worked from came from "one of the islands of the South Pacific Ocean", and said that "its manners and habits are unknown".12 Julius von Haast, the German-born explorer who first described his namesake eagle from fossilized remains, also described the kākāpō more fully, noting that even in 1862 its range was significantly reduced from earlier days.13

- Bunbury, Magdalena M.E., Fiona Petchey, and Simon H. Bickler. “A New Chronology for the Māori Settlement of Aotearoa (NZ) and the Potential Role of Climate Change in Demographic Developments.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 119, no. 46 (November 6, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2207609119.

- Pimm, Stuart. “No More Moa.” Nature 420, no. 6914 (2002): 361–61. doi:10.1038/420361A.

- Perry, George L.W., Andrew B. Wheeler, Jamie R. Wood, and Janet M. Wilmshurst. “A High-Precision Chronology for the Rapid Extinction of New Zealand Moa (Aves, Dinornithiformes).” Quaternary Science Reviews 105 (2014): 126–35. doi:10.1016/J.QUASCIREV.2014.09.025.

- Ashworth, James. “The World’s Largest Eagle Hunted Unlike Any Other Bird of Prey,” Natural History Museum, last modified November 30, 2021, https://www.nhm.ac.uk/discover/news/2021/december/worlds-largest-eagle-hunted-unlike-any-other-bird-of-prey.html.

- Brockie, Bob. “Introduced Animal Pests.” https://teara.govt.nz/en/introduced-animal-pests.

- Lazarus, Sarah. “Can Tech Save the Kakapo, New Zealand’s ‘Gorgeous, Hilarious’ Parrot?” CNN, December 26, 2019. https://www.cnn.com/2019/12/26/world/kakapo-conservation-scn-c2e-intl-hnk/index.html.

- Salvador, Rodrigo B. “Douglas Adams and the World’s Largest, Fattest and Least-Able-to-Fly Parrot.” Journal of Geek Studies. Last modified February 24, 2019. https://jgeekstudies.org/2018/10/17/douglas-adams-and-the-worlds-largest-fattest-and-least-able-to-fly-parrot/.

- Lloyd, Brian D., and Ralph G. Powlesland. “The Decline of Kakapo Strigops Habroptilus and Attempts at Conservation by Translocation.” Biological Conservation 69, no. 1 (December 31, 1993): 75–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/0006-3207(94)90330-1.

- Dussex, Nicolas, Bruce C. Robertson, Love Dalén, and Erich D. Jarvis. “The Kākāpō (Strigops Habroptilus).” Trends in Genetics (February 28, 2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tig.2022.03.004.

- “Kākāpō Return to Mainland in Historic Translocation.” https://www.doc.govt.nz/news/media-releases/2023-media-releases/kakapo-return-to-mainland-in-historic-translocation/.

- Domonoske, Camila. “Call The Pied Piper: New Zealand Wants To Get Rid Of Its Rats. All Of Them.” NPR, July 25, 2016. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2016/07/25/487362815/by-2050-new-zealand-aims-to-be-rid-of-rats-stoats-and-possums.

- Gray, George Robert. The Genera of Birds Vol. 2 (1845): 426-428. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/43661630#page/269/

- von Haast, Julius. "on the Birds of New Zealand." Ibis Vol IV: 103-104. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/page/8330687

Curation Links

The Blurb Problem Keeps Getting Worse | Helen Lewis, The Atlantic

“Blurbs” are those quotes on the back of books from people who read and enjoyed them. A book without blurbs is at a serious disadvantage, and authors are a clannish sort prone to looking out for one another, so there’s a lot of pressure to provide a blurb to a friend’s new book. Enough pressure to drive the creation of false blurbs, written of books the quoted person hasn’t actually read, and, more widely, overly kind blurbs written of books the quoted person perhaps found just okay.

An Old Conjecture Falls, Making Spheres a Lot More Complicated | Kevin Hartnett, Quanta Magazine

"There are different types of progress in math and science. One kind brings order to chaos. But another intensifies the chaos by dispelling hopeful assumptions that weren’t true. The disproof of the telescope conjecture is like that. It deepens the complexity of geometry and raises the odds that many generations of grandchildren will come and go before anyone fully understands maps between spheres."

How a TV Works in Slow Motion | The Slow Mo Guys

[VIDEO] “If you are reading this, you've seen a screen with your eyes. But have you REALLY seen it though? Like real proper seen it? Don't worry, Gav is here to help you out. This is How a TV works in Slow Motion.” (11:39)

Bartleby, the Scrivener: A Story of Wall-Street | Herman Melville

[FICTION] From the author of *Moby Dick*, the story of a man who seems to "prefer not to" do anything. This classic work is often taught as a study in clinical depression before such a term was used.

See the full archive of curations on Notion

Member Commentary