Running Commentary 8/14/2023

Hello,

It's still not peak birding season, but I happened to see three green herons in one place this past week. They're skittish and small, so while they're around, they're tough to spot. I got very lucky.

Anyway...

Watching...

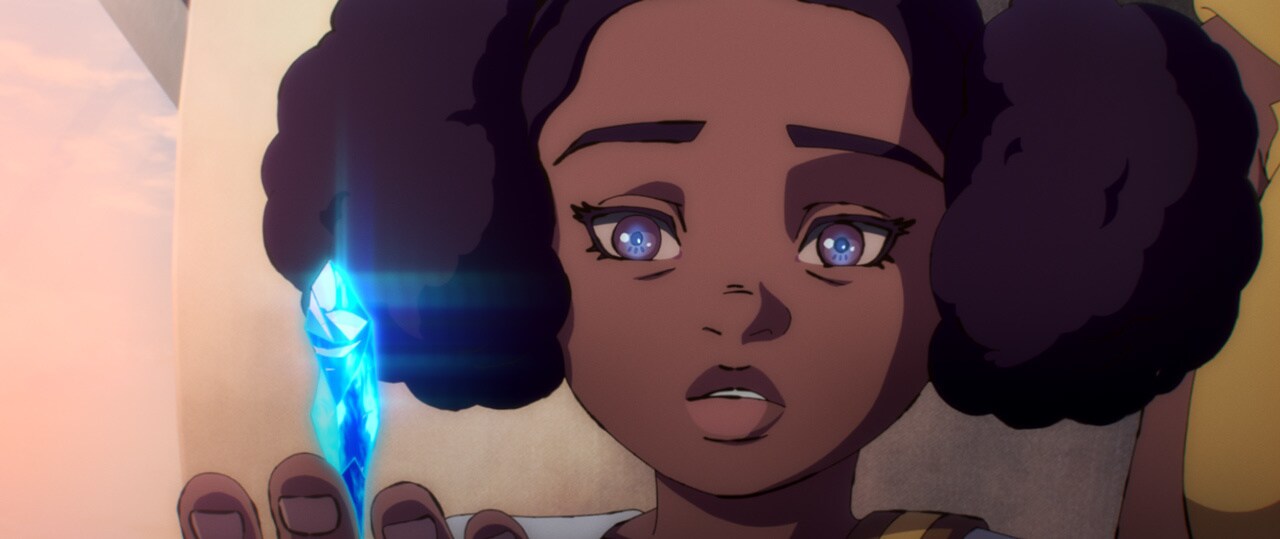

Star Wars: Visions

"The Pit" is a Visions entry from Japan...kinda. Here are my notes:

- I say "from Japan...kinda" because while D'art Shtajio is based in Japan, it's American-owned, and the writer and director of this short is LeAndre Thomas, an American (and LucasFilm employee), so this is more an American project that a studio full of Japenese workers brought to life. Which is ironic considering what the short is about, really.

- I think this short works better thematically than in the literal particulars. The story of Imperial citizens discovering the way the Empire drove industrialization of their world on the back of forced laborers is a a decent enough idea for a short, but when you see those laborers digging a massive open-pit mine with pickaxes and nothing else, it doesn't make sense. And when you see their plan to get the people of the city to come help them come down to rescue them is basically to all yell really loud and hope they're heard, that also doesn't work. The music and animation worked, the theme almost worked, but they actual sequence of events shown felt very rough draft.

- I will not be adding Daveed Diggs to the List, since he's actually been in Star Wars before, voicing Duros spy Norath Kev in an episode of Resistance.

Reading...

Knowing What We Know by Simon Winchester

Knowing What We Know is the latest book from Simon Winchester, who some of you might recognize as the author of The Perfectionists, one of my favorite non-fiction books. This is actually the fourth book of his that I've read. This book is a history of the transmission of knowledge, a broad scope, but one which Winchester breaks down into smaller chunks and tackles more or less chronologically. There's a brief look at oral traditions before and equally brief look at the emergence of writing, in Mesopotamia, then a longer look at the history of formal schooling (as a great deal of knowledge transmission is between generations). There's a history of the book, the library, the museum, the encyclopedia, the internet. There's a look at the still-developing world of artificially intelligent researching machines able to review and summarize the great mass of knowledge humanity has amassed. There's also discussion of attempts to stifle or distort knowelge through censorship or propaganda. Winchester does narrow his definition of knowelged to essentially verifiable facts, leaving discussion of things like cultural mores and works of fiction largely unmentioned.

The book is, as ist ot be expected from Winchester, an engaging and informative read. But, I'm sorry to say, I don't think I'll be recommending it. Ironically this book just doesn't transmit much knowledge. It's not a completely worthless read, but a lot of what's in it is either obvious or otherwise pretty well-known. People like Aristotle or Johannes Gutenberg and Tim Berners-Lee get mentioned ,but all theat's really said about them is what's always said about them. Generally I'll come away from a Winchester book with some new understanding of something, that I can pass along. I didn't hate reading the book but I also didn't get much out of it.

The one thing that Winchester adds is a pretty clear articulation of a particular sort of egghead worry thatthat as knowledge is increasingly stored in easily accessible and well-indexed ways that people will cease to actually learn things and retain them themselves, and that similarly skills involving thinking will continue ot be automated and mechanized until learning becomes equally as outmoded as yarn-spinning and butter churning. For people like Winchester, learning and teaching others are the core elements of the human condition, so it's understandable that the suffestion that machines might do so as well or better (thus far an unproven theory but not one that can be entirely dismissed out of hand) would be so upsetting. Winchester holds a largely pessimistic view of AI research, predicting it will not be so great a benefit to humanity that the printing press was.

But overall, as a history, I don't really think Knowing What We Know is worth reading. There's just not enough to it. Winchiset admits in the last pages that the book largely served to occupy his time during the COVID-19 pandemic, which might go a ways in explaining why it's so preoccupied in tone. I'd look into any of several other books Winchester's written over this 5/10/

Bird of the Week

This week we have another icterid, one of the "jaundiced" New World songbirds so named because they're commonly yellow-colored somewhere. We've had icterids with yellow heads, yellow eyes, yellow wingbars, orange feathers (orange was considered a shade of yellow back in the day) and now we have one with a yellow tail. The chestnut-headed oropendola is one of nine species of oropendola, birds characterized by–and indeed named for, as in Spanish oropéndola is a portmanteau of the words for "gold" and "quill"–yellow feathers on the undersides of their tails. Most oropendolas also sport streamlined casques over their beaks, making them look as if they'd put an experimental new bike-racing helmet on backwards; the casque of the chestnut-headed is the largest relative to the rest of it.

Oropendolas are native to Latin America, with the chestnut-headed specifically being found on the east coast of Central America from southern Mexico down into Colombia and Ecuador. Included in its home range is the Magdalena River, which is best known to some as the last route taken by the famed South American revolutionary Simón Bolívar before his death from arsenic poisoning (in turn due either to the poor quality of medicines available in the early 19th century or due to the deliberate action of political rivals, depending on who you ask). The chestnut-headed oropendola's range is one of the most bird-rich regions in all the world, home to thousands of species.

Oropendolas and their close cousins, the caciques, build large hanging nests woven from grass and other plant fibers. These nests are "apartment-style", with multiple cavities for multiple females to lay eggs in. Generally, several dozen nests are hung in close proximity to one another. And preferably, they'll be hung in close proximity to wasp or bee hives, since these scare away botflies. One of the more disturbing parasites affecting vertebrates, botflies lay their eggs on the skin of various creatures, including humans and oropendola hatchlings, and their larvae burrow into the skin and flesh of the host. In humans this is little more than a nuisance, but in oropendola chicks an infestation can be fatal. Oropendolas not living near beehives have been observed to be more permissive toward cowbirds, a species that lays its eggs in the nests of other birds. The cowbird chicks instinctively preen their nest mates, clearing their skin of botfly eggs. As oropendolas don't share this instinct, the cowbird chick is typically the one to succumb to infestation.

As I mentioned, the word "oropendola" comes from the Spanish "oropéndola", a mash-up of "oro", meaning "gold", and "péndola", which means "quill". But the word also means "pendulum" or "hanger", which is the more common Spanish meaning of the word today. The fact that these birds create pendulous hanging nests is coincidental. To science, the chestnut-headed oropendola is Psarocolius wagleri; the generic name references the starling and the jackdaw, two European birds of similar appearance to the oropendolas, while the specific name references Johann Georg Wagler, a German biologist who studied under Johann Baptist von Spix, a major figure in South American ornithology. Wagler himself contributed much to ornithology, though he died at just 32 from an accidental self-inflicted gunshot.

Curation Links

Why is North up? | Jay Foreman & Mark Cooper-Jones, Map Men

[VIDEO] A humorous but informative look at the history of one of the more universal social conventions: depicting maps with northern regions at the top of the sheet. It wasn’t always that way, and it sometimes still isn’t. (10 minutes)

School Is Not Enough | Simon Sarris, Palladium

“It is difficult to blame young adults for thinking that work is fake and meaningless if we prescribe fake and meaningless work for the first two decades of their existence. When meaningful work is an adult-only activity, it is little wonder that adolescence is a period of great depression. It would be surprising if it was not. Unlike the past, where many smart children finished sooner, modern education endlessly ushers them towards an often farther and more abstract future—one so far away and abstract that some children become infected with the opposite of agency. They take on a learned helplessness and downplay that the future is a reality at all.”

1945: Fair Warning | The U. S. Army Air Forces, Lapham's Quarterly

Likely in reference to the recent release of a biopic on J. Robert Oppenheimer, *Lapham's Quarterly* re-upped this: the text of leaflets dropped on Japan between the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs, calling the emperor to end the war or, barring that, evacuate the cities.

Dispatches Regarding the Woeful Origins of the Town’s Bicycle Race | Tom Froh, The Walrus

"Bad news. The wolves in the nearby provincial park have finally mastered the use of bicycles. It was only a matter of time. Everyone—town local and park beast alike—envies the beautiful out-of-town cyclists who swarm the trails this time of year. The taut, hairless perfection of their thighs and sleek racing suits make us all feel like slobs, given to degenerate practices like eating gluten and encountering air resistance. It has taken the pack a few months to get the hang of the machines, during which many gorgeous cyclists were menaced and their bikes stolen. The Park is full of discarded tires lying like snakeskin along the trails, and its visitor centre teems with recently mugged city folk, their faces exquisite even in sorrow."

See the full archive of curations on Notion

Member Commentary