Running Commentary 3/3/2025

Hello,

I haven't seen a single bufflehead this winter, and, it now being March, I think I might not see any before they head back to Canada. Checking eBird, it seems like it was a bust year for them in general.

Also, if you're anywhere in the Saugatuck/Holland MI area, there are two quite rare vagrant waterfowl at Lake Michigan: a barnacle goose and a tufted duck, both in from Europe. These are too far for me to want to travel to see them but if you're at all nearby it's worth a look.

Anyway...

Reading...

Force by Henry Petroski

I've read a couple of Petroski's other books (The Pencil and The Evolution of Useful Things) and there are several others on my to-read list. Force: What It Means to Push and Pull, Slip and Grip, Start and Stop is the latest book from the retired engineering professor, and I'm sorry to say I found it quite disappointing. This book is meant to be a guide to physical forces for a non-engineer audience. As someone who is an engineer and has had formal instruction in forces and mechanics I might not be the one to appreciate this, but this book really does seem to be a little too dumbed-down. Or not even dumbed-down, really just vague and rambly. A lot of it is just Petroski describing his day in terms of force analysis, to no clear educational effect: from page 114:

Every evening, after making sure the cats are inside and the doors locked, I prepare for bed by brushing my teeth. This involves some of the trickiest maneuvers I will have done with my hands all day. Just to get a dab of toothpaste out of the tube and onto my toothbrush involves picking up the tube, unscrewing its cap, setting it down, picking up my brush, positioning it under the opening of the tube, pinching the tube to coax out a dab of paste, replacing the cap, laying down the tube, grasping the brush, moving it back and forth and up and down and around and around in my mouth, turning on the water, moving the brush every which way under the faucet to rinse it off, placing it back in its holder—in other words, combinations of grasping, twisting, squeezing, pinching, pushing, and pulling motions that my hands segue among while I am thinking about none of them. I do not even have to think about how hard I am brushing, because I have learned to do so lightly enough that I do not erode tooth enamel but aggressively enough to dislodge food from between my teeth and around my gums, as well as produce enough friction between bristles and enamel to polish the surface to a tongue-pleasing sheen.

Petroski’s writing is often full of tangents, but he generally is telling a story of some sort; there isn’t really a story to be told of forces, so there’s not really a core to hold this book together. Petroski thus is left to talk about his cats, or the Washington Monument, or COVID-19 without any coherent idea other than stating that forces exist over and over.

This book demonstrates that Petroski is undoubtably interesting conversation but I can’t recommend it the way I can the other books of his I read, mostly because it’s frontloaded with inane accounts of squeezing toothpaste tubes and walking down hallways. There’s no real meaningful exploration of force in Force. Mostly there’s simple mention of things like friction, gravity, or leverage, described at, honestly, a middle-school level. It feels like what it is: a retired professor’s way to keep himself busy during a pandemic. I didn't get much out of it. 4/10

Bird of the Week

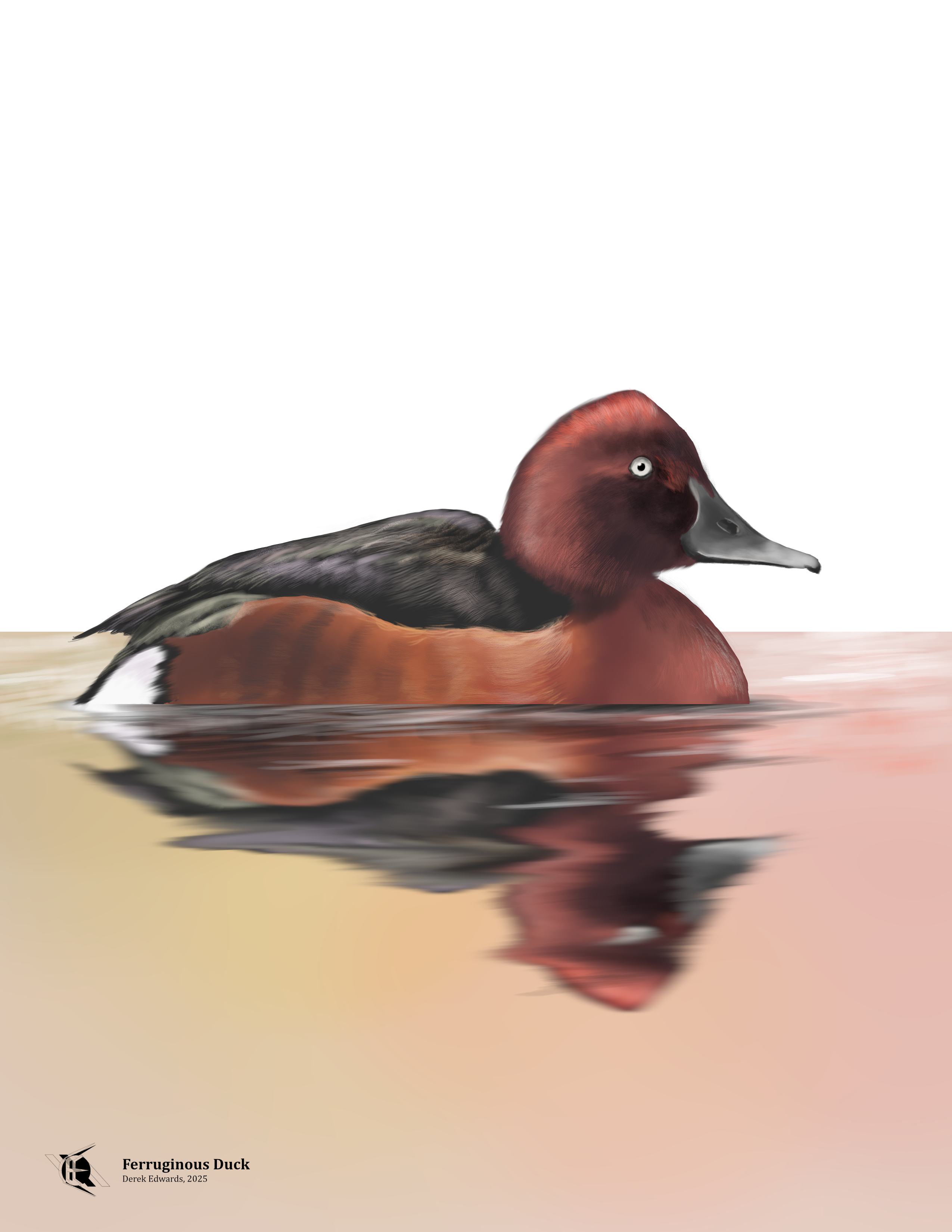

Most birds are brown. Most vertebrates, really. Brown is an odd color; it's not on the color spectrum; it's not a hue. It's the name we give to dull shades of warm hues, those from yellow to red. Brent Berlin and Paul Kay, anthropologists who studied the development of color terms, listed brown as the seventh color named in most languages, getting named just after blue and before other non-hue colors like pink and gray. (I should mention that Berlin and Kay loosened their initial theory, and the fact that a language doesn't have a particular word for "brown" doesn't mean that its speakers don't have a conception of brown).1 Besides being a non-primary color and coming late to our vocabulary, brown has struggled to get much respect from artists. Brown is made from very cheap pigments like umber and ochre, or else by blending together multiple pigments and arguably wasting them. A few artists championed brown, but most prided themselves if they could avoid using it in their works. In more practical uses, brown has served as the color of the poor.2 And yet, as someone who lives in the post-scarcity world of synthetic dyes and digital painting, I think it's time we admitted that brown can indeed be beautiful, and I think there's no finer argument for this position than today's bird, the Ferruginous Duck.

A member of the pochard genus, the ferruginous duck is a widespread yet somewhat local diving duck of Eurasia and northern Africa. It breeds in marsh ponds in a very fragmented breeding range spread through pockets of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, mainly; in the off-season, it becomes much more widespread, migrating south for the winter to some areas but mostly moving out into areas of open water generally, where it forms mixed flocks with other pochards and scaups. The Ferruginous Duck feeds mainly on aquatic plants, though they have been known to eat aquatic invertebrates on occasion.

In a chapter about shorebirds, the birding writer Kenn Kaufman described the term "semipalmated" as "a term no one but bird people use".3 (It means, as of the feet of a plover and a sandpiper species, "half-webbed"). "Ferruginous" is a term used by no one but bird people and rock people. It comes from the Latin for "rust" and ultimately from the Latin for iron: ferrum. Incidentally, that's the term by which early chemists knew iron, which is why the metallic element is abbreviated "Fe" on the Periodic Table. Rock people use it to refer to minerals and soil that contain iron oxide; bird people use it to refer to birds with reddish-brown feathers: besides this duck, there is a ferruginous hawk and a ferruginous pygmy-owl. Those who find "ferruginous" too difficult to spell might, on occasion, prefer to use the bird's alternate name: white-eye, referencing the drake's conspicuous and distinctive white iris. (Although take care not to get it confused with the Pacific songbirds known as white-eyes.)

To science, the bird is Aythya nyroca. The genus name, applied to the pochards and scaups, is taken from Classical Greek texts where it referred to a water bird, though which one is unclear. The species name was given by Johann Anton Güldenstädt, a German-speaking naturalist born in Riga – today the capital city of Latvia – who served as an explorer of the Caucasus region under the patronage of Catherine the Great of Russia. He found the duck, which Linnaeus had overlooked, in the Tannais region, on the shores of the Sea of Azov; he gave it the name nyroca, from "nyrok," the Russian word for "pochard."4,5

- Rogers, Adam. Full Spectrum: How the Science of Color Made Us Modern. Mariner Books, 2021. pp.147-149.

- St. Clair, Kassia. The Secret Lives of Color. Penguin, 2018. pp.237-239

- Kaufman, Kenn. The Birds That Audubon Missed: Discovery and Desire in the American Wilderness. Simon and Schuster, 2024. p.240

- Jobling, J. A. (editor). The Key to Scientific Names in Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman et al. editors), Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca.

- Güldenstädt, J. A. "Anas nyroca", Novi commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae. Petropolis: Typis Academiae Scientarum, 1748. p. 402. https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/9527.

Curation Links

The Jagged, Monstrous Function That Broke Calculus | Solomon Adams, Quanta Magazine

“The proof demonstrated that calculus could no longer rely on geometric intuition, as its inventors had done. It ushered in a new standard for the subject, one that was rooted in the careful analysis of equations. Mathematicians were forced to follow in Weierstrass’ footsteps, further sharpening their definition of functions, their understanding of the relationship between continuity and differentiability, and their methods for computing derivatives and integrals. This work to standardize calculus has since grown into the field known as analysis; Weierstrass is considered one of its founders.”

The Comet Panic of 1910, Revisited | Sam Kean, Distillations

Halley's Comet passes within sight of the Earth every 76 years, never really without incident, but not often inspiring as much dread as it did in 1910, when the new science of spectroscopy revealed cyanogen and hydrogen in the comet's tail, leading to wild claims that it might poison the whole planet or else turn our sky to water, drowning and asphyxiating us all at once. (We made it unharmed.)

If the Reagan Airport crash was “waiting to happen,” why didn’t anyone stop it? | Ari Schulman, The New Atlantis

“Two questions then should confront the country as we reckon with the Reagan Airport crash and work to prevent the next ‘just a matter of time’ air disaster. First: What can our air safety system do differently to patch these holes proactively? The answer must go beyond the *oh-no-what-were-we-thinking* window of opportunity for change that only briefly follows a disaster. It must mean understanding why air safety leaders ignored so many pilots warning of exactly this disaster — and figuring out how to change the incentives to make leaders actually seek those pilots out. And second: Does the air safety system bear the ultimate blame here? Or did the military, hurried members of Congress, government officials eager to please VIPs, the perplexing design ideas of the Dulles planners, and the public itself place so many competing demands on the airspace around the Potomac that disaster truly was just a matter of time? If the answer is yes, then the air safety system might just be an easy scapegoat for a broader rot, and we could be setting ourselves up for this to happen again.”

Light Speed is Not a Speed | Andy Dudak, Clarkesworld

[FICTION] “‘Picture a man on a camel loping along at fifty miles an hour. The mounted piece fires a gunstone at a hundred miles per hour. How fast is the gunstone moving when it strikes you? You’re stationary. You’re standing there like a dolt.’ Lig snorts. ‘Hundred and fifty miles per hour?’ ‘Right.’ ‘I’d become a fine mince. You could sell me in pies.’ ‘And if you were running toward the gunstone at ten miles per hour, because you’re just that foolish?’ ‘One-sixty. So . . . ’ ‘Light is different, they say. Always moving at light speed.’ ‘You lost me, El.’ ‘If it’s true, it means . . . ’ He can’t put into words what he’s thinking, but he pictures light moving, independent of reference frames. ‘If it’s true, then light speed is not a speed. I could fly like a bullet toward a star, or a torch, and the light hitting me would still be moving at light speed. It doesn’t add up.’ ‘What doesn’t?’ ‘Light!’ Lig clutches his stomach. He heads for the stinking, buzzing necessary down the lane—three-bit per use. El gives up trying to explain himself. His thoughts race, approaching light speed, never quite getting there. If light speed is not a speed, what is it? A context, he thinks. But for what? For everything.”

See the full archive of curations on Notion

Member Commentary