Running Commentary 10/28/2024

Hello,

My Merlin Bird ID app from Cornell gave me a heads up that a lot of ducks were moving through my area, and, when I made a quick afternoon tour of local duck ponds, I found they were quite right. I saw a tremendous amount of ducks Saturday, from hooded mergansers to greater scaups to shovelers, all mostly from very far away. But the prize was this male northern pintail that I spotted; it being October, he didn't have his namesake long tail, but there's not mistaking that slim build and long neck, even from

Remember that my Birding Log (linked to from the top of the page) includes ID tips for all the birds I've seen/am actively looking for, as well as quick diary accounts of birding excursions. Here's the entry for my duckspotting tour.

Anyway...

Reading...

The Truth and Other Stories by Stanisław Lem

Stanisław Lem is an odd figure in the history of sci-fi. He was Polish, and wrote in Polish, but much of his work has been translated into English and other languages; he was probably the writer of non-English sci-fi most widely read by Anglophone readers, at least pre-Cixin Liu. In the introduction to this collection of short stories, Kim Stanley Robinson (author of the Mars trilogy) mentions how Lem held American/Free World sci-fi in disdain, somewhat, though Robinson points out that Lem had not widely read sci-fi from the other side of the Iron Curtain, and that much of what he did read were not exactly enduring classics of the genre. In any case, Lem's works stand out just for their quality but, for American readers, their separateness from the main sci-fi tradition.

Despite claims by Philip K. Dick that Lem was a Soviet Bloc propagandist, Lem was not really a devoted Communist. Of course, the Polish people were pretty badly treated by the Soviets – in his twenties, Lem and his town were all deported from what became Ukrainian territory after WWII – so this shouldn't be a great shock. While he certainly wasn't any sort of Americophilic capitalist either, he was, at least from what I can tell from his writings here, more individualistic than collectivistic. His stories aren't really hero-and-villain stories, but they generally portray individuals as the story agents, where groups and institutions are generally shown as ineffectual at best, sinister at worst.

Lem's stories here are tried-and-true sci-fi ideas: alien invasions, robots, artificial intelligences. The one really odd idea comes in "Darkness and Mildew", which is about bioengineered bacteria that consume all matter. But Lem's stories are not as straightforward as you might expect. His aliens, for instance, are not mere Men from Mars; they are genuinely alien, their motives and thoughts unknown, unclear whether they are people or spaceships or both. The one sort of exception comes in "Invasion from Aldebaran", but this is a satire on space exploration stories rather than an alien invasion story, really. Each story feels like a commentary on whatever sort of story it is.

There are twelve stories, presented oldest to latest. The first and oldest, "The Hunt", Lem didn't like, and is certainly not the best of the collection, but pretty soon things pick up. My two favorites are "The Friend" and "One Hundred and Thirty-Seven Seconds"; both of these deal with artificial intelligence, but in quite different ways.

"The Friend" is actually quite an early example of a story about a general artificial intelligence becoming an evil god-like entity. It has much better-developed characters than Lem’s other stories. What exactly is going on, and who the titular “friend” is, is a mystery that is well set up and well paid off; that’s a lot of good suspense packed into this story. When the narrator is integrated into the AI’s consciousness, the shift in narration style is suitably jarring and grandiose without becoming incomprehensible. I will say that as far as Chekov’s Guns go, the melting solder was less hung on the wall as mounted behind glass marked, in large stenciled letters, “Break in Case of Final Act”; by the actual climax you’ve forgotten about it enough to make it exciting, but at the time it’s introduced it is obviously setting something up for the end.

"One Hundred and Thirty-Seven Seconds" is very interesting in a less overtly terrifying yet more realistic way. As an AI story, it’s less about a terrifying electronic deity like what featured in “The Friend” or “The Journal”, and more about something like the generative AI boilerplate writers that are emerging into the market today; of course the theory underlying these systems date back to around when this story was written, and it’s only the more recent proliferation of digital training data available online that’s enabled it today. The prescience of the AI is more fanciful than the rest of the concept, but it’s plausibly explained.

The worst was "The Journal": Page after page of tedious metaphysical psychobabble followed by a few paragraphs trying to give it context. This wasn’t engaging at all, never seeming to get around to saying whatever Lem was trying to.

The quality of the translation I can't really speak to, not being able to compare the English to the original Polish, both because I don't have the originals and because I can't read Polish, but I will say that I didn't find the language awkward, so I suppose translator Anatolia Lloyd-Jones did her job well in that respect. Incidentally, Solaris, the novel generally considered Lem's magnum opus, apparently has a very poor English translation, prepared from the French translation; Lem's estate has commissioned a direct English translation but have struggled to get it published.

Anyway, The Truth and Other Stories is a good look at Lem's talent and thoughtful creativity. I'd be interested in reading one of his longer works someday. Not every story here was fantastic, but ten of the twelve were at least quite good.

Bird of the Week

When you look into birds, one of the first things you find is a range map. These are a mainstay of the modern field guide; they were not a feature of the original Perterson guide from 1934; they were a feature of the 1977 edition of the Audubon Society's Field Guide to Birds of North America; I'm afraid I'm not sure who first featured a map of where each bird lived, but, whoever was first, the practice is now ubiquitous. Birders now take them for granted, trusting that they give at least a general idea of where birds can be found. But how do they make these maps? It's not like human population maps, which are based on census data, or like political maps, which are based on legally defined boundaries. No, range maps emerge from a roiling soup of anecdotal reports. People see birds in a given location, report that somehow, and if enough people see it enough times in a given place, that place becomes part of that bird's range. Sometimes scientists make a more technical effort to evaluate a range, as in the satellite surveys of emperor penguins,1 but mostly they let the millions of people who seek out birds as a hobby report what they see and build their data from that. This, along with netting and banding sessions, provide data points which, when aggregated and plotted, become range maps. In the Internet Age, these maps can be quite detailed, but they'll never be finished, because, after all, a range isn't determined by people; it's determined by birds. And birds are, as a rule, notoriously mobile creatures. Take, for instance, today's bird: the Scissor-tailed Flycatcher.

Perhaps the most distinctive of all the tyrant-flycatchers, the scissor-tailed flycatcher is generally said to be a bird that breeds in the southern Great Plains and winters in Central America. And that's pretty well true. During the summer, if you really want to see one, you can go to Texas or Oklahoma or bordering areas and find them there. During the winter, go to the Pacific Coast between Mexico and Panama, and you'll find them there. That's their range. But it's also possible to be almost anywhere in North America and find one there. A sighting isn't likely, or consistent, but it's possible. Scissor-tailed flycatchers are quite commonly seen as "vagrants", a term used for birds that travel outside their usual range.

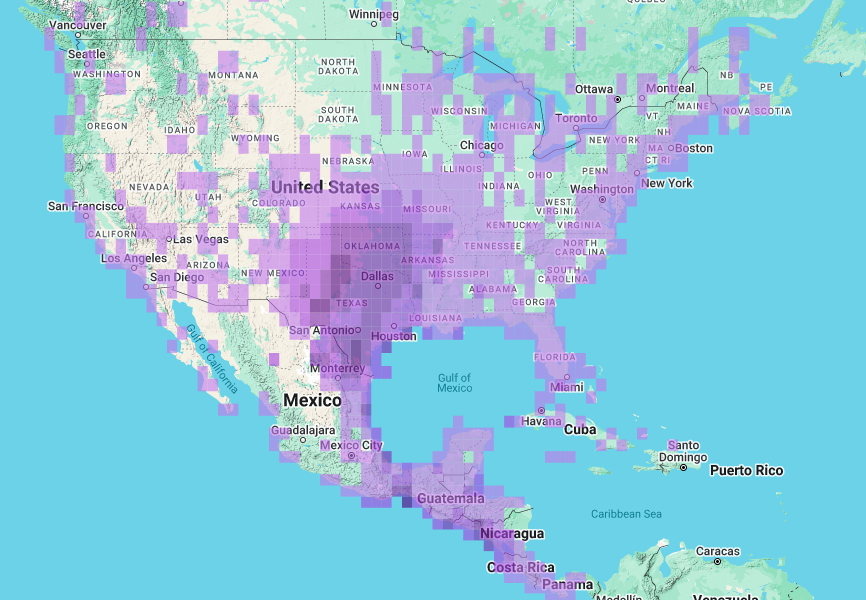

Distribution map of the scissor-tailed flycatcher from eBird Status and Trends2 (left) and map of eBird observation reports (right)

Now, any number of birds, flying birds particularly, can become vagrants, but scissor-tailed flycatchers seem to have a special knack for showing up where they "aren't found". Sometimes I think that its distinctive look is why it's such a known vagrant; if a Cassin's finch was to wander east of its range, anyone who saw it would probably take it for a house finch and go on with their day, but if you see a scissor-tailed flycatcher, even if you're far from it's official range, you'll know right away what you're looking at. And so you get more reports of vagrant scissor-tailed flycatchers than of other, more non-descript birds. Birders in northern Ohio, for instance, have reported at least one scissor-tailed flycatcher there for the past several years. Just one at a time, but not zero, as you'd expect from looking at its range map.

I was inspired to draw this bird because one recently visited Michigan, near the lakeshore at Ludington, too far for me to journey on the off-chance of seeing it still there, but close enough for me to have heard the news. But the bird had been on my list ot draw for a while. It is, as I mentioned, an incredibly distinctive bird, with pale salmon underparts and the long namesake tail, it's two points held together when perched, splayed own wide in flight, very much as if its tail was a pair of scissors. The tail is generally longer in males than in females, but its length varies greatly by individual; a bird with a medium-length tail (such as I've drawn) might be a short-tailed male or a long-tailed female. Sometimes the bird will be given the tongue-in-cheek name "Oklahoma bird-of-paradise", as if one of the long-tailed birds of Australasia had found itself in the Sooner State. Now, that would be a vagrant! Oklahoma, for their part, have named the scissor-tailed flycatcher their official state bird; as an emblem, it is also featured on the box of the bird-themed board game Wingspan.

To science, the bird is Tyrannus forficatus. The species name means "scissor-shaped", from the Latin "forfex", meaning "scissors" or "shears"3; the Romans were the first to make what we'd recognize as scissors: two blades hinged in the middle. The genus name, first applied to the eastern kingbird, is that Latin word from which we get the English "tyrant"; originally it referred to a usurping king. The word also got used in Star Wars: Darth Tyrannus was a Sith Lord who sought to usurp the rule of the Galactic Republic until, in a weird connection to this bird specifically, he was beheaded by a pair of lightsabers held crossed, like scissors.

- Wienecke, B, Jl Lieser, Jc McInnes, and Jhs Barrington. “Observed Repercussions for Emperor Penguins of Fast Ice Variability in East Antarctica.” Endangered Species Research, January 1, 2024. https://doi.org/10.3354/esr01355.

- Fink, D., T. Auer, A. Johnston, M. Strimas-Mackey, S. Ligocki, O. Robinson, W. Hochachka, L. Jaromczyk, C. Crowley, K. Dunham, A. Stillman, I. Davies, A. Rodewald, V. Ruiz-Gutierrez, C. Wood. 2023. eBird Status and Trends, Data Version: 2022; Released: 2023. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, New York. https://doi.org/10.2173/ebirdst.2022

- Jobling, J. A. (editor). The Key to Scientific Names in Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman et al. editors), Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca.

Curation Links

The Genius Who Launched the First Space Program | Sven Etienne Peterson, Palladium

Profile of Sergei Korelev, who led the Soviet space program that launched *Sputnik* and Gargarin, as well as a look at how, even to this day, space programs become entwined in the images of their charismatic leaders.

Door closers: ubiquitous, yet unloved and often maladjusted | Technology Connections

[VIDEO] A look at door closers, found on most swinging doors in buildings besides private homes but often overlooked (or underlooked, maybe, since they sit above eye level, I dunno). How do they work? What is their history? And how can their performance by adjusted? (24 minutes)

Apostrophe's Dream | Yiyun Li, The Dial

[FICTION] The punctuation marks in a typesetter’s drawer question what to name themselves, collectively. Not a fascinating story but seeing how the different symbols are characterizes has a certain Flatland-ish charm.

See the full archive of curations on Notion

Member Commentary