Running Commentary 1/13/2025

Hello,

There are some short-eared owls that have taken up in a field near enough to me to be worth going to check even if they don't show themselves. I was there early yesterday morning, but it was foggy and they weren't showing themselves. (I got there a bit late but another birder who had been there since before sun-up hadn't seen them either). Short-eareds are a crepuscular owl, not a nocturnal one, so they're worth searching for at dawn or dusk. There's a serious snow coming to the area tonight that I think will drive them further south, which means I have one more chance this evening. Hopefully they're there.

Anyway...

Watching...

Skeleton Crew

- We've made it back to At Attin, and it is indeed home to vaults full of Old Republic credits. I must say that I find it a little strange that Old Republic credits are worth so much when the government that issued and backed them isn't around anymore. I guess it does seem like they're made from

goldaurodium, so they could just be valuable as precious metal, but I'd rather think that these pirates have contacts on the numismatist scene willing to pay big for out-of-print money. - We end the episode on a bit of a cliffhanger leading into the finale, but besides that there are two big things left for the show to resolve: the people of At Attin need to learn that the Republic they serve no longer exists, and we, the audience, need to finally learn what Jod's background regarding the Jedi is.

- Jude Law's performance as he finally finds his vault of credits is one of the best bits of acting Star Wars has ever had.

- Add Stephen Fry to The List.

Reading...

The Dispossessed by Ursula K. Le Guin

I mentioned at the end of my "Thirty Years of Waru" piece that after spending last year reading mostly mediocre-to-bad Star Wars novels, I wanted to spend this year reading more things generally regarded as good-to-great. First up on this (actually read toward the end of last year) is The Dispossessed. Here are my notes on it:

- Le Guin subtitled this book “An Ambiguous Utopia”, which I think sets up what the book is pretty well. The book deals with a lot of political ideas, and features multiple utopian societies, that is, societies organized in complete accordance with some philosophy or another, but none of these are presented as good, or as something Le Guin is personally endorsing; they are ideas that she is exploring. The point of the book is to get the reader thinking about the societies presented, and about their own society, much more so than it is to present a society to either emulate or shun.

- The story is that of Shevek, a scientist from the moon of Anarres. Generations ago, the moon was settled by exiles from the world of Urras, followers of a woman named Odo who preached an anarchistic, hyper-individualistic philosophy. The Odonians live without a government and without much material wealth on the barren moon, reliant on mining to trade for necessary supplies from Urras. The planet of Urras is divided into three nations: the collectivist dictatorship of Thu, the unstable, developing country of Binbilli, and the stratified, very wealthy land of A-Io; these roughly correspond to the Sino-Soviet Bloc, the Third World, and the Free West of the Cold War era during which the book was written.

- While Le Guin does not idealize the world of Anarres, she does make an earnest attempt to produce a society with no leadership that still manages to function, at least in the sense that Anarres is not a power vacuum wherein the people are at the simple mercy of whoever is the biggest (despite an early scene in which an infant Shevek is deprived of sunlight by a larger child and subsequently chastised for being upset about it). I think that a lot of the peaceableness of Anarres comes more from authorial fiat than from a logical understanding of the world; I might believe that Odonian philosophy simply abhorred violence too much for it to be a problem, at least in that I’m suspending my disbelief enough to read about people from outer space, except that there’s a scene wherein Shevek is nearly killed by a person with a similar name upset that the two were getting confused, so clearly that’s not the case. In any event, the book isn’t about how an anarchist society handles murderers, but about how it handles scientists.

- The book is told in alternating chapters: odd ones taking place in the book’s present, when Shevek is the first of his people to return to Urras (in order to present a groundbreaking scientific theory); even ones telling Shevek’s life story up until that point. Each chapter is fairly long; there are thirteen in total. Shevek is increasingly dissatisfied in his life on Anarres, but while on Urras, he grows increasingly disgusted by the people of A-Io and their society of consumption and conflict.

- A-Io is the less interesting of the two societies shown in the book; it is essentially a society made up of what Le Guin found distasteful about her own society, exaggerated, and stripped of much goodness; they’re rich, at least the scientists Shevek is put up with are; even the poor we see are rich by Anarresti standards. Not a lot is said about them other than that they are vain and materialistic.

- The Odonian society is without any formal authority or power structure, although, as Shevek’s life plays out, he comes to realize that Anarres does have an ersatz government made up of influential figures positioned at social chokepoints, something analogous to the early Roman emperors who, legally, were private citizens with no formally delegated power, and yet used their influence to guide the Roman state. The Odonians also lack possessions, not just materially, but going so far as to avoid anything that could be described with a possessive adjective, including friends and family. By official dogma, all Odonians are family to one another, but as a practical matter on Anarres no one really matters much to anyone else, as we see when bystanders ignore Sheved trying to kill Shevek, and as we see in the character of Rulag. A big turning point for Shevek is when he decides to defy the demands of his society to live a life with Takvar, a woman who he loves and has had a child with before the computer system that gives work assignments split them up, sending them to opposite sides of Anarres. That they stay separated for four years speaks to how aberrant close personal relationships are on Anarres.

- The work-delegating computer is probably the most dated element of the book, a rather hand-wavy attempt to explain how critical administrative functions happen on Anarres without a government. I suppose that it’s not impossible for a computer to operate as it is described here but it reflects and idea of ~50 years ago that computers would be perfectly fair and impartial that seems quite naive today. It’s unclear who maintains the computer, which brings us to something that surprised me:

- I was convinced that it would be revealed that, from an Urrasti perspective at least, the people on their moon were their slaves. We’d seen that Urras trades with Anarres for metals, ores for which have long since been depleted on Urras; the Anarresti miners provide the foundation of Urrasti wealth while living in often fatal poverty, but because they’ve abandoned the notion of earning or deserving anything, they don’t even know to complain about the arrangement. Everyone on Anarres is encouraged to work; even children are shown to labor to some extent. Those who don’t wish to work or who defy the computer’s assignments, though they formally have every right to, a socially ostracized. Those who can’t work due to illness are similarly shamed. We don’t see any Anarresti who are disabled or elderly. When Shevek returns from a journey to find Taker had been assigned to another settlement and that he’ll likely never see her or their child again reminded me strongly of real-world episodes from the Antebellum South of families broken up when some of them were “sold down the river”. On Urras, Shevek is mainly kept around the very wealthy, and he keeps wondering where the poor, which he knows are part of the Urasti system, are being hidden. I kept thinking that the Urrasti hide their poor on the moon. But that wasn’t what the book was building towards, and would have sort of ruined the point Le Guin was trying to make about Anarres: that the Anarresti were responsible for themselves, and that they had become complacent. Externalizing their problems to be Urras’s fault, even if that’s likely partly true, would undercut this.

Bird of the Week

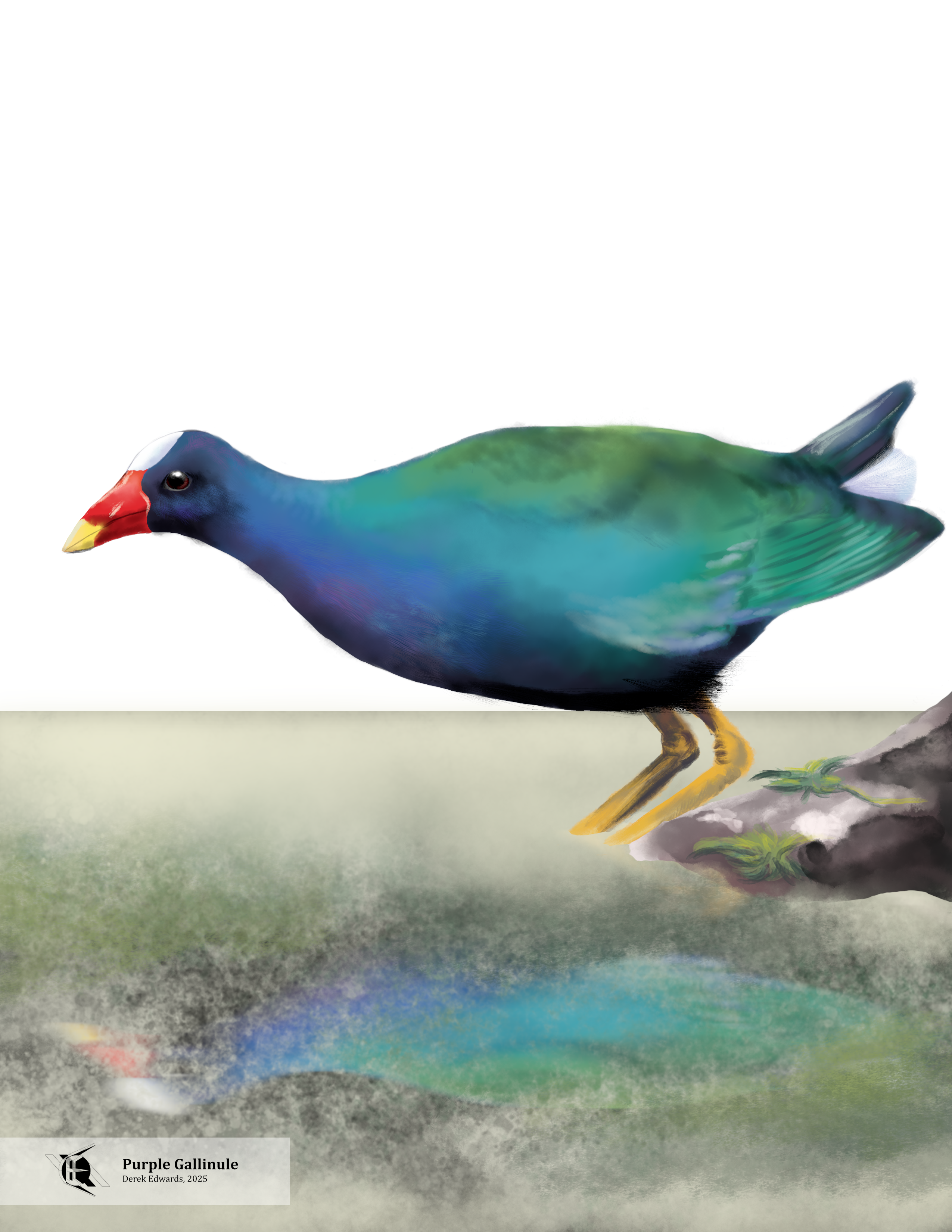

In the past year, I started keeping track of just which birds I've actually seen. I got into birding more through drawing birds than through watching them, which isn't really the typical path, so I didn't really have my life list written down anywhere. Once I sat down to do so, I was faced with the somewhat daunting task of categorizing all the world's birds into two groups: those I've seen and those I haven't seen. Not being much of a traveler, I was able to quickly place most of the world's birds in the "haven't seen" group. I started with just a list of birds reliably found in the United States, eliminated birds endemic to Hawai'i out of hand (I haven't been there) and set about going bird-by-bird among those left and marking the one's I'd seen. American robin? Of course, I see those all the time. Carolina wren? That's a regular visitor outside my window, just infrequent enough to be special. Cliff swallow? No, I'd remember seeing that, if I had. Limpkin? Ah, yes. I've seen one once, when it came well north of where it was supposed to live. And so on down the list. But there are birds that don't quite fit neatly in "seen" or "haven't seen", such as today's bird, the Purple Gallinule.

I can confidently say that I have seen a common gallinule, the purple's darker, more widespread cousin. Gallinules, also sometimes called moorhens or swamp-hens, are relatives of the coots and rails. They are something like the mid-point between chickens and ducks, though they are actually in the crane order, Gruiformes. They have large, unwebbed feet and bullet-nosed beaks that often feature a "shield" that partially covers their forehead. Gallinules (whose name comes from the Latin for "small hen"1) are wetland specialists, not generally found on open water but always in or near marshy ponds. Gallinules tend to be blue-green, either darkly, almost blackly or else brightly so, like the purple gallinule, which is probably the most colorful non-songbird in North America.

Purple gallinules range extends from South and Central America up into the U.S. Southeast, though it's not unheard of for it to make it as far north as the Great Lakes.2 It's not impossible for me to have seen one here in Michigan. Have I? I'd like to think so. In August of 2020 I made my first trip to the Shiawassee National Wildlife Refuge, one of the finest birding destinations in Lower Michigan. There I saw something fly out of a bush next to a flooded ditch. It was a large bird – not huge but too big to be a songbird – and it was a bright shiny blue with a red beak. It looked like a purple gallinule, for the split-second that I saw it. And yet, I can't say for certain that it was. Again, while purple gallinules have been found in Michigan, they're quite rare here. Granted, if they do show up, Shiawassee NWR is just the place they'd go, but none have ever been reported there. Common gallinules are regularly found in Michigan; I've personally definitely seen them at Shiawassee, one that same day and once again since. Common gallinules are a very dark blue-green, almost black, but if the light caught one just right, it might look bright blue, if one only saw it fleetingly.

That day, I marked the bird I saw on eBird as a common gallinule, and when I made my list, I left the purple gallinule unmarked as "seen". I can't honestly claim to have seen a purple gallinule based on a little flash of blue and a lot of wishful thinking. I also can't claim to have seen a Kirtland's warbler based on some yellow streaky underparts and a broken eyering spotted back in the trees on a golf course last October. There are many birds that I might have seen, but I won't list them until I've definitely seen them. (Or heard them, but that's a story for a different bird.)

To science, the purple gallinule is Porphyrio martinica. The genus name comes from an old Latin term for a swamp hen3, first applied to the western swamphen of Europe, which are a reddish-purple where the purple gallinule is a bluish-green; the term comes from the Greek term for that reddish-purple. Doctors or other readers familiar with medicin may recognize Porphyrio as nearly the name of a medical disorder: porphyria is a blood disorder that can cause nervous system issues and severe pain. While the underlying cause (a buildup of chemicals in the body due to improper production of hemoglobin) was unknown to them, the ancient Greeks recognized porphyria as a disease, giving it its name due to the phenomenon (discovered in what must have been fascinating circumstances which are now lost to history) that an affected person's urine would turn reddish-purple if left in a glass jar in sunlight for a few days.4,5,6

- “Gallinule.” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/gallinule. Accessed 12 Jan. 2025.

- O’Brien, Isoo. “eBird Checklist - 7 May 2023 - Pipe Creek Wildlife Area - 113 Species.” eBird, May 7, 2023. https://ebird.org/checklist/S136511973.

- Jobling, J. A. (editor). The Key to Scientific Names in Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman et al. editors), Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Ithaca.

- Mayo Clinic. “Porphyria - Symptoms and Causes,” n.d. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/porphyria/symptoms-causes/syc-20356066.

- Pathobiology of Human Disease: A Dynamic Encyclopedia of Disease Mechanisms (Elsevier, 2014), 1488.

- Chen, Guan Liang, Deng-Ho Yang, Jeng-Yuau Wu, Chia-Wen Kuo, and Wen-Hsiu Hsu. “Neuropathic Pain in Hereditary Coproporphyria.” Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences 29, no. 2 (March 11, 2013). https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.292.3202.

Curation Links

Why we fell for clean eating | Bee Wilson, The Guardian

A look at “orthorexia”, an eating disorder built around overly-strict dietary rules, and the way a specific sort has spread as the hopeful (and lucrative) trend of “eating clean”.

The Great Lightbulb Conspiracy | Markus Krajewski, IEEE Spectrum

“The cartel’s grip on the lightbulb market lasted only into the 1930s. Its far more enduring legacy was to engineer a shorter life span for the incandescent lightbulb. By early 1925, this became codified at 1,000 hours for a pear-shaped household bulb, a marked reduction from the 1,500 to 2,000 hours that had previously been common.”

The Butterfly King | Becky Milligan, Exactly Right

[AUDIO] “When King Boris III of Bulgaria dies amid mysterious circumstances during World War II, there's no shortage of suspects. But eighty years later, his death remains unsolved. Award-winning journalist Becky Milligan follows a trail of dissidents, poisoners, soldiers and spies to unravel eighty years of lies and cover-ups. This tragic family saga of a doomed royal dynasty is a story of treachery, deceit and a quest for the truth. Who killed the Butterfly King?” (8 episodes, about 50 minutes each)

Good Night, Sleep Tight | Brian Evenson, Electric Literature

[FICTION] A father worries that his mother, when staying with his family, will tell his young son the scary bedtime stories she told him as a boy.

See the full archive of curations on Notion

Member Commentary